Stephen M Hornby

Stephen M Hornby dramatises archives for stage and screen, revivifying the past and finding forgotten stories that demand to be heard. He is the Artistic Director of Inkbrew Productions, his multiple award-winning creative company based in Manchester. They specialise in making LGBTQ+ heritage performances working in theatres, galleries, museums and embedded in communities bringing the queer past to life to illuminate the present.

He is a lecturer at the University of Salford leading classes on playwriting, scriptwriting and directing. He is honoured to have been the first LGBT+ History Month Playwright In Residence since 2015.

Productions

Here are details of our world-leading performance work, exploring the queer past. Our main production partner is Inkbrew Productions. We work with Schools OUT, as well as other creatives, historians and heritage organisations on a project-by-project basis. There are pictures of each production, blogs from the creative teams and announcements about future events.

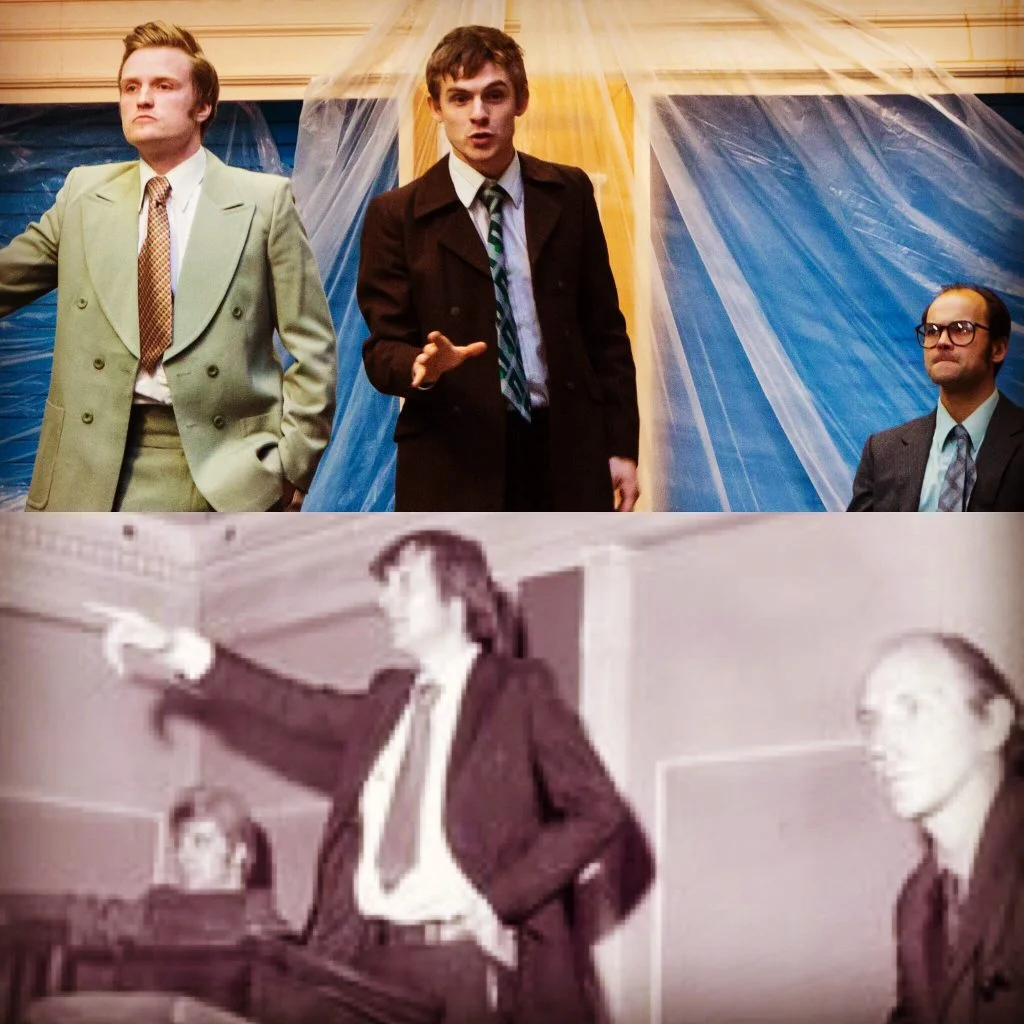

2026 Heritage Play – “The BBC’s First Homosexual”

Inkbrew Productions is delighted to continue its partnership with SchoolsOUT for LGBT+ History Month with a new play The BBC’s First Homosexual, written by Dr Stephen M Hornby and directed by Oliver Hurst. The play is touring extensivel throughout February 2026. It reveals the story of a forgotten landmark moment in queer broadcasting history.

In 1954, the BBC produced its first ever documentary on male homosexuality – a groundbreaking radio programme that was so controversial it was banned and shelved for three years. When it finally aired in 1957, only a heavily edited version was broadcast, and the original recording was subsequently lost. All that remained was a forgotten transcript, recently rediscovered after more than seventy years.

With the BBC’s permission, this historic document has now been brought to life on stage by multiple-award-winning writer Dr Stephen M Hornby. Originally commissioned for the BBC 100 celebrations, Inkbrew Productions will present the newly expanded The BBC’s First Homosexual as part of an extensive tour as the official heritage premiere for LGBT+ History Month.

Known for creating plays from archive material, our Playwright in Residence, Dr Stephen M Hornby was granted unique access to BBC archive materials including the original transcript, internal memos, and letters from the public in response to the programme. He said:

“I’ve woven fragments from the BBC’s archive with the fictional story of a young man exploring his own life. Through him, audiences see what life was like being gay in the 1950s and the impact the documentary has upon him. Several so-called ‘experts’ in the programme supported conversion therapy, and its influence on British society is still felt today. I suspect this partly explains why we are still campaigning to ban such practices.”

Bringing these characters to life on stage are Mitchell Wilson (Rob & The Hoodies, Vienna’s English Theatre; Down The Lines, South Shields Customs House; Birdsong, JH Films) as Tom, northern actor Max Lohan (The A List, Netflix; FBI International, NBC/Universal; The Enfield Poltergeist, Apple TV), who currently plays Callum in Emmerdale (ITV) and renowned panto dame Andrew Pollard (Whatever Happened to Phoebe Salt, New Vic; A Leap In The Dark, New Vic; Hollyoaks, Lime Pictures; Trying Again, Sky One/Avalon; Emmerdale, ITV; Spooks: Liberty, BBC / Kudos Television).

Film: Tinsel Town (Sky Original Films)

The historical research for the play was carried out by Marcus Collins, Professor in Contemporary History at Loughborough University, who said:

“This brilliantly insightful play illustrates the dilemmas LGBTQ+ issues created for the BBC in the 1950s. The broadcaster had to overcome its aversion to discussing anything to do with sex, while navigating pressures from gay activists, religious groups, and the public. The compromise it reached, though imperfect, helped shape how lesbian, gay and trans people saw themselves and how they were seen by the wider British public.”

Oliver Hurst, Artistic Director of Red Brick Theatre and director of the play, added:

“Bringing this documentary and era to life is a thrilling challenge. With Stephen’s brilliant script and our talented cast, we are offering audiences a truly exceptional theatrical experience.”

Following opening performances at the New Adelphi Theatre in Salford, (4th and 5th Feb), the Crescent Theatre in Birmingham (6th Feb) and the Lantern Theatre in Brighton (7th and 8th Feb), The BBC’s First Homosexual the play will arrive at The Cinema Museum in London (10th to 14th Feb). The production will continue to Hope Street Theatre in Liverpool (17th and18th February); before concluding at Loughborough University (24th and 25th Feb). Tickets for all venues start from £5 and are available here: https://linktr.ee/inkbrewtheatre

“The Day The World Came To Huddersfield” new short film released online

The UK’s first ever national Pride took place in Huddersfield on 4th July 1981. To mark the fortieth anniversary, a series of arts events are taking place up until September 2022, an arts and archive, multi-media celebration of a milestone in the LGBTQ+ history of the UK.

In February 2022, one of the original shops on the Pride march route, 8 New Street, was used for a unique exhibition as the first part of this project was delivered. 8 New Street was chosen as the shopfront has changed so little since 1the 1980s. A four-minute film was made by Hanging Boots Creative using recovered pictures from the 1981 march, some new portraits taken by Ajamu X, both of the LGBT+ community that marched in 1981 and who live in Huddersfield today, some specially commissioned animations, and words written by Stephen M. Hornby, a playwright working on the project. The film was projected on to the shop front for the whole of LGBT+ History Month 2022.

The archive elements were from pictures recently donated to the West Yorkshire Archive Service and from the Robert Workman Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute in London. Kirklees Council, a partner on the project, estimates that the footfall for February of people passing the shop whilst the film was being projected was over 100,000 people.

The response has been so positive that the projected elements were then reconfigured into a short film that anyone can now enjoy on the LGBT+ History Month YouTube site by clicking #Pride1981 short film

The project moves on now to the next two elements:

- Photographic Exhibition: Internationally renowned photographer Ajamu X has taken a series of 20 portraits of people who marched in 1981 and people who are part of the LGBTQ+ community in Huddersfield today. Ajamu was born in Huddersfield and saw the original Pride 81 march. The exhibition will run at the Lawrence Batley Theatre from 9th July to 9th September 2022. After that, the portraits will become a part of the permanent collection at Huddersfield Art Gallery.

- Immersive Performances: Inkbrew Productions will create an immersive performance recreating Pride 1981 in Huddersfield Town Centre on 2 July 2022. The audience will be participants in the march, co-creating the piece with actors playing activis, who tell their stories as they march. Ten monologues written by award winning playwrights Stephen M Hornby, Abi Hynes, Peter Scott-Presland (an original Pride 81 marcher) and Hayden Sugden form the heart of this piece. They will also be performed as a showcase at the Lawrence Batley Cellar Theatre, Huddersfield and the Kings Arms, Salford from 1st-3rd July 2022.

2022 National Heritage Play – Awards for Pride 1981 show

“The Day The World Came To Huddersfield” has won two awards and been nominated for a third. The show won the GM Fringe Award for Best Drama, the inaugural Queer Lit prize for Best LGBTQ+ Production and was also nominated for an Off West End award for Best Short Run Production.

Stephen M.Hornby, writer and producer on the show said:

“We sold out. We got great reviews. And now this! These awards are for everyone involved in the shows. The visionary directors: Helen Parry and Olivia Schofield. The amazingly talented cast: Simon Hallman, Jude Leath, Emily Spowage, Patrick Price, James Steventon, Nathan Morris, Jo Dakin, Martin Green, Iman Borono and Sapphire Brewer-Marchant. All the inspirational writers: Abi Hynes, Peter Scott-Presland and Hayden Sugden. And, of course, our hard working crew: Sabine Sulmeistere, Luke Harrison and Chloe Davies. We’re all very honoured and thankful.”

2022 National Heritage Play – Pride 1981 show sells out to fantastic reviews

“The Day The World Came To Huddersfield” projects celebrates Pride 1981, the first time a Pride was held anywhere outside London. The performance exploring the characters and events of that Pride has been a huge critical and audience success, selling out all the performances.

London Pride organisers decided to move the march to Huddersfield that year in protest against the police’s repeated raids on a local gay bar, The Gemini. The Gemini was the North of England’s best loved gay club and people would travel from miles around to the Huddersfield venue. Back before there was much of a night life for the LGBTQ+ community in nearby cities of Sheffield, Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester, Huddersfield was the place to be.

Inkbrew Productions have commissioned the 10 monologues to capture the story of the Pride 1981 march based on the startling characters and compelling histories that they’ve unearthed, many for the first time. The monologues were written by award-winning playwrights Stephen M Hornby, Abi Hynes, Peter Scott-Presland (who was on the original Pride 1981 march) and Hayden Sugden.

“The Day The World Came To Huddersfield” was staged at the Lawrence Batley Cellar Theatre, Huddersfield and the Kings Arms Theatre, Salford from 1st-3rd July 2022. The performances were funded by the Arts Council of England, Kirklees Council and Schools Out/LGBT+ History Month UK.

“I cannot remember the last show I saw with a large cast in which every single actor shone. Although the actors were brilliant, praise for this must also go to the writers; such captivating tales with a common theme but so different in tone. We were taken on an emotional journey and were so invested in every character, the true mark of good writing.” – Reviewer No 9

Every character in the performance was perfect…This is a must see.” Ancoats Plus

“I can’t remember when such an equally strong cast, 10 in all, performed to such a high standard …Bravo to everyone involved in this production.” – Canal-St Media

“An immersive theatrical experience that deserves to be treasured.” – North-West End

2022 National Heritage Play – BBC News Coverage

The UK’s first ever National Pride took place in Huddersfield on 4th July 1981. To mark the forty-first anniversary, an immersive theatre event called “The Day The World Came To Huddersfield” restaged the Pride march in Huddersfield Town Centre. Actors joined their audience to become the protesters, shouting slogans and waving placards and banners. As the march progressed, the actors told the stories of the people who marched that day.

Inkbrew Productions, OUTing the Past’s production partner, have commissioned the 10 monologues that make up the show to capture the story of the Pride 1981 march based on startling characters and compelling histories that they’ve unearthed for the first time. The monologues are written by award-winning playwrights Stephen M Hornby, Abi Hynes, Peter Scott-Presland (who was on the original Pride 1981 march) and Hayden Sugden.

BBC News reported on the recreation on their website and BBC Radio 5 Live interviewed two of the writers about the work and the experience of being a part of the project.

The street performance recreating the original march assembled in the courtyard outside the Lawrence Batley Theatre at 2.00pm on Saturday 2nd July. The circular route through the town centre included parts of the original Pride 1981 march route. That march set off from the Huddersfield Town AFC ground and the football club was represented on the march by Terriers Together.

The project is funded by the Arts Council of England, Kirklees Council and LGBT+ History Month UK. There are several different strands to it which you read about on other blogs on this site, including archive work with West Yorkshire Archive Service and new portrait exhibition from Ajamu X.

2022 National Heritage Play – “The Day The World Came To Huddersfield”

The UK’s first ever national Pride took place in Huddersfield on 4th July 1981. To mark the fortieth anniversary, a series of arts events will take place from now until July 2022, a yearlong multi-media celebration of a milestone in the LGBTQ+ history of the UK. The events have been made possible by funding from the Arts Council of England, Kirklees Council and LGBT+ History Month UK. Social media for the project uses “#Pride1981”.

There will be three main elements to the celebration:

- Photographic Exhibition: Internationally renowned photographer Ajamu X will take a series of 20 portraits of people who marched in 1981 and people who are part of the LGBTQ+ community in Huddersfield today. Ajamu was born in Huddersfield and saw the original Pride 81 march. In February 2022, there will be a Street Exhibition of some of the portraits at key parts of the original Pride 81 route (bus stops, billboards and buildings). The full set will then be displayed at the Lawrence Batley Theatre from 1 June to 31 August 2022. After that, they will become a part of the permanent collection at Huddersfield Art Gallery.

- Immersive Performance: Inkbrew Productions will create an immersive performance recreating Pride 1981. The audience will be participants in the march, co-creating the piece with actors playing activists from 1981, who tell their stories as they march. Ten monologues written by award winning playwrights Stephen M Hornby Abi Hynes and Peter Scott-Presland (an original Pride 1981 marcher) form the heart of this piece. They will also be performed as a showcase at the Lawrence Batley Cellar Theatre, Huddersfield and the Kings Arms, Salford from 1-3rd July 2022.

- On-line Archive of Pride 81: the West Yorkshire Archive Service (WYAS) & Heritage Quays are making a call-out to capture personal photographs of the 1981 march. Digital copies will become stored as a permanent part of each archive. WYAS will be holding the first of two Pride 81 Submission Days at Kirklees Archives Pop-Up opposite Huddersfield Library on Saturday 25th September, 11am-4pm. People can turn up and have their pictures scanned and returned.

To start the yearlong celebrations, on 4th July 2021, Kirklees Council dressed the original route of the march with the Pride rainbow on lighting columns, beginning at the junction of Leeds Road and Bradley Mills Road and ending at the south gate of Greenhead Park.

Professor Sue Sanders, OUTing The Past said: “This is an extraordinary project. The first national Pride in Huddersfield in 1981 is a wonderful piece of forgotten history that needs to be known across the UK. These excellent events will not just create some wonderful new art and performances, they will leave a legacy for Huddersfield, a lasting memory of its own past.”

Ajamu X, Huddersfield born photographer said: “It’s very special to me to be able to take these portraits celebrating the hidden queer history of my hometown. As a 17 year old, stood on street corner watching the Pride 81 march go by, I had no idea of the life that lay ahead of me. To return now to celebrate that moment is a unique opportunity to show the true diversity of communities in Huddersfield.”

Stephen M Hornby, Playwright and Artistic Director of Inkbrew Productions said: “The Pride march of 1981 was full of extraordinary characters from Huddersfield and from across the country. And the stories! It’s a treasure trove for playwrights and Abi and I can’t wait to get started. We hope some local writers will be joining us to rediscover what marching in the UK’s first national Pride felt like.”

Councillor Will Simpson, Cabinet Member for Culture and Greener Kirklees, said: “As this year’s Pride month comes to an end, I’m so pleased we can announce our yearlong plans to commemorate and celebrate the 1981 Pride march in Huddersfield. The 1981 march is unique piece of – often forgotten – Huddersfield history. I’m extremely pleased that we have been able to plan these engaging events so that we can collectively celebrate this significant moment in our history.”

Free Films for LGBT+ History Month 2021

In the 1970s, Burnley was the UK’s battleground for gay and lesbian rights. Who knew, right?! To mark the 50th anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act (1967), LGBT History Month commissioned two brilliant new dramas from Inkbrew Productions to rediscover this amazing forgotten history. Both productions were made possible with funding from the Arts Council England and from our generous patron, Russell T Davies.

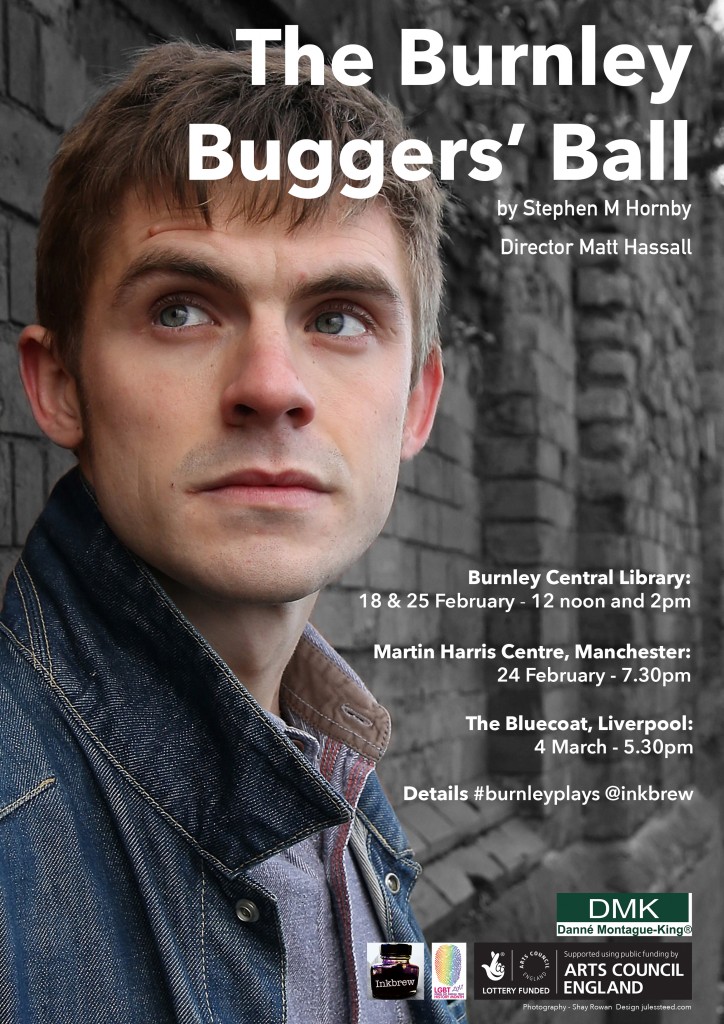

The Burnley Buggers’ Ball, by Stephen M Hornby, tells the story of a transformative political meeting held at Burnley Central Library in July 1971. The play was staged in the actual space that the meeting was held in, thanks to the support and kindness of Lancashire County Council who brought it out of retirement for this production. The production featured a professional cast in the main roles and a supporting cast from the wonderful Burnley Youth Theatre. Director Matt Hassall created an amazing immersive experience for the audience who become the attendees at the infamous meeting and had to decide whether to, “Stand up if you’re gay!”.

Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator by Abi Hynes dramatises the political activism of Mary Winter, a bus driver sacked for nothing more than wearing a badge, a badge that said, “Lesbian Liberator”. Suspended by management and unsupported by her union, Mary organises a picket of the Burnley Bus Station to protest her case and draw a line to inspire others. Helen Parry’s skillful direction of the piece draws the audience into the narrative of the Mary’s grievance and then invites them to become activists in her cause, to take up banners, chant and attend a rally outside within a few meters of the where the original rally took place at the entrance to Burnley Bus Station.

2019 National Heritage Play – tour is a huge success!

“The Adhesion of Love” is a play by Stephen M Hornby commissioned by OUTing the Past as our 2019 heritage premiere. It is the first full-length heritage premiere and was made possible with grants from the Arts Council of England and Manchester Pride’s Superbia.

The play is based on the extraordinary true story of how an architect’s assistant from Bolton crossed the Atlantic in 1891 to meet visionary queer American poet, Walt Whitman. It was written with extensive research by Hornby using archive materials that relate to the Bolton Whitmanites in both Bolton Library and the John Rylands Library in Manchester.

The play was toured across the North West of England as part of LGBT History Month and for the celebrations of Whitman’s 200th birthday, providing a challenging queer reading of the past.

This tour of “The Adhesion of Love” generated local, regional and national press interest, with over 15,000 people engaging with articles about the play on-line. There were full preview articles in the following publications:

- Gay Times (two page feature piece, print)

- Attitude (on-line)

- Bolton News (print and on-line)

- Burnley Express (print and on-line)

- Gay Star News (on-line)

- Big Issue North (print)

- Queerist (on-line)

The play toured to Bolton, Salford, Burnley, Manchester and Wigan. The final performance in the Bolton Socialist Club was on the 200th birthday of Walt Whitman. The club itself was visited by the men featured in the play and was a brilliant place to end the tour with a sell-out performance.

The tour attracted the largest audience for any heritage premiere with nearly 500 people attending. The audience response was impressive. 201 anonymous after show questionnaires were completed in total. 119 (59.2%) gave the show five stars. 71 (35.3%) gave the show four stars. So, overall an amazing 94.5% rated the show as either excellent or very good.

This was reflected in the quality, depth and length of the after-show discussions chaired by Paul Fairweather. People testified to the impact of the show in terms of re-thinking not just a specific piece of history but also about the process of how history is made and recorded, especially in relation to LGBT+ people.

The critical responses spoke of the high artistic quality of the production:

· “Nothing short of a triumph.” – Burnley Express

· “The actors are all excellent. Go.” – Canal St

· “The play is a thoroughly researched mediation on loss, love, and literature.” –Reviewer No 9

· “A great evening’s entertainment.” – Greater Manchester Reviewer

· “This really does feel like a step back into another era.” – Live Art Live

· “It’s a truly fascinating story.” – Circles & Stalls

2019 National Heritage Play – “The Adhesion of Love”

LGBT History Month is thrilled to annouce Inkbrew Productions “The Adhesion of Love” as the 2019 national heritage premiere for LGBT History Month. The play will be touring venues in Greater Manchester & Lancashire from 9 February to 31 May.

Written by multi-award winning playwright Stephen M Hornby, The Adhesion of Love tells the extraordinary true story of how an architect’s assistant from Bolton crossed the Atlantic in 1891 to meet the visionary queer poet Walt Whitman. The production builds on previous National Heritage Premiere successes: The Burnley Buggers Ball & Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator (2017); Mister Stokes: The Man-Woman of Manchester & Devils in Human Shape (2016); and A Very Victorian Scandal (2015).

In 1885, John W Wallace, a working-class man from Bolton, sets up the Eagle Street ‘College’, a book group that celebrates his love for Walt Whitman’s poetry. Attracting a small group of like-minded men, Wallace embarks on a journey of spiritual and sexual self-discovery through Whitman’s words. When Wallace arrives in America six years later and meets his literary hero face-to-face, he is forced to confront the true nature of the intimacy the college members are seeking. On his return to Bolton, Wallace is unsure how to express his new sexual and spiritual awakening within in the conservative confines of Victorian England.

Stephen M Hornby, playwright in residence to LGBT History Month, Artistic Director of Inkbrew Productions and writer of The Adhesion of Love says: “Bolton’s connection with Walt Whitman, whilst surprising, is documented and celebrated in Lancashire. But the true nature of the intimate meetings of men at the Eagle Street College has been kept hidden from view. The Adhesion of Love attempts to reclaim ‘comradely love’ as what I believe it really was – men attempting to express their true desire for one another in a sexually repressive society – as well as posing the question: if LGBT people had been able to write their own history, what would it look like?”

Matt Cain, writer of The Madonna of Bolton, patron of Bolton Pride and LGBT History Month, journalist and author says: “The Adhesion of Love is a gripping and fascinating play about a group of characters whose stories aren’t widely known but very much ought to be. It’s vital that this play is performed in Bolton, the town in which it’s largely set, not just to reclaim the area’s LGBT past but also to make all parts of the UK more LGBT-inclusive places to live in the present.”

Professor Sue Sanders, Chair and founder of LGBT History Month UK says: “George Orwell said: ‘The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.’ I founded LGBT History Month as LGBT people in all their diversity were still invisible, especially in the past. Theatre is a crucial part of LGBT History Month and enables people to learn, through the heart as well as the head. I’m thrilled that Stephen is back dramatising new and surprising LGBT history for our celebrations in 2019.”

2019 is also the bicentennial of Whitman’s birth and this full-length play offers an amazing new insight into his work and influence on the UK.

The Adhesion of Love is supported by Arts Council England, Superbia and LGBT History Month.

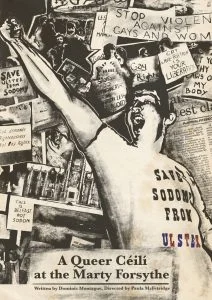

“A Queer Céilí At The Marty Forsythe” is coming!

A Queer Ceili at the Marty Forsythe is an exciting new production from Kabosh that explores the events of the first National Union of Students Lesbian and Gay Conference, Queens University Belfast 1983. This is the first heritage premiere produced in the new partnership between Kabosh and LGBT History Month.

One year after the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Northern Ireland, and two years after the 1981 hunger strike, the events of that weekend are a remarkable chapter in the city’s LGBT history.

Upon arriving at Queens University Students Union, conference delegates from across Ireland and the UK were greeted by a large-scale protest from the ‘Save Ulster From Sodomy’ campaign. This crusade was still in full force despite its recent defeat in trying to hold Northern Ireland behind the rest of the UK in legalising homosexuality.

As hostility echoed from outside the Students Union and tensions mounted within, with pressure from the NUS National Executive threatening to cancel the event and evict the delegates from their digs, the conference was in danger of receiving anything but a warm Irish welcome.

That was about to change……

Delegates were offered an invitation from the community in West Belfast to join them at the Martin Forsythe Social Club in Turf Lodge, an invitation that was eagerly accepted. In the early evening of Saturday 22nd October 1983, a convoy of Belfast’s famous black taxis transported delegates to an event they could never have expected, and one they would never forget. That evening turned into one of the most remarkable and supportive LGBT events any of the young delegates had ever experienced, and the most unique céilí Belfast had seen.

Set against the soundscape of 1983 Belfast: the escalating Troubles; vocal and violent opposition to homosexuality; and a thriving punk scene, A Queer Ceili at the Marty Forsytheis an exploration of a unique chapter in Belfast’s history, and a celebration of commonality and camaraderie in the face of adversity.

The world premiere of this production will take place in the Trinity Lodge, formerly The Marty Forsythe where the 1983 céilí was held!

Produced by Kabosh in partnership with LGBT History Month. Written by Dominic Montague and directed by Paula McFetridge. A premiere with the Imagine Belfast Festival of Ideas and Politics. Funded by Arts Council Northern Ireland, Belfast City Council, Community Relations Council NI, and The Halifax Foundation.

A Queer Céilí at the Marty Forsythe

Venue: The Trinity Lodge, Monagh Grove, Belfast, BT11 8EJ

Dates: 27th-30th March 2019

Time: Doors 7:30pm, performance starts at 8pm

Kabosh announced as Irish LGBT History Month heritage performance partner for 2019

LGBT History Month is delighted to announce that Kabosh will be joining Inkbrew Productions as an official production partner, creating heritage performance premieres. Kabosh is an independent theatre company focused on giving voice to site, space and people through creating new theatre in interesting places using the history, stories and buildings of Northern Ireland as its inspiration.

Founded in 1994, Kabosh is committed to challenging the notion of what theatre is, where it takes place and who it is for. From site specific theatre animating space and exploring native narratives (West Awakes, Belfast Bred) to theatre as a catalyst for social change (Those You Pass On The Street, Green & Blue, Lives in Translation) Kabosh is dedicated to exploring and giving voice to the unique character of the locations and communities in which they work.

Through ground breaking work such as Two Roads West (a piece of immersive theatre staged in a moving taxi) to Built To Contain (a radio play created by ex-prisoners exploring their experiences of incarceration), Kabosh has explored new ways of presenting human stories, challenging preconceptions and provoking change.

Their recent production Quartered: Belfast, A Love Story, written by Dominic Montague, is an immersive audio theatre journey exploring the contemporary LGBTQ+ experience of Belfast and the complex relationship between identity and space. Premiering with Outburst Queer Arts Festival in November 2017, it has been restaged through 2018 and was nominated for Event of the Year at the Belfast Pride Awards 2018.

Dominic Montague, Project Facilitator at Kabosh said, “We’re delighted to start work in partnership with LGBT History Month on unearthing the rich and distinct queer history of Ireland. We are dedicated to exploring vital stories yet untold and look forward to working as a sister company to Inkbrew Productions in England.”

Twitter: @KaboshTheatre www.kabosh.net

2018: Playing With The Past

Stephen M Hornby and Abi Hynes, two of our Festival Theatre playwrights, gave a talk at the People’s History Museum in Manchester as part of their OUTing the Past Festival for 2018. They talked about four plays and how they’d researched archives and worked with historical adviser to create compelling and popular drama that was also historically literate drama. Here’s an edited transcript of what they said.

STEPHEN: I want to start five years ago in 2013, when Russia was poised to stage the Winter Olympics. More and more evidence was emerging from Russia of their oppression and state sanctioned violence towards the LGBT community, but with them promising a spectacular games, no one, least of all the British Olympic Committee, was interested in a boycott. So, me and a group of fellow theatre makers decided we’d do what we do best, and we made a play about it. To Russia With Love was the umbrella title for four short pieces by me, Chris Hoyle, Rob Ward and Adam Zane which were staged in Space 1 at Contact in Manchester in February 2014. This brought me as a playwright and producer to the attention of Dr Jeff Evans, the National Festival Coordinator for LGBT History Month.

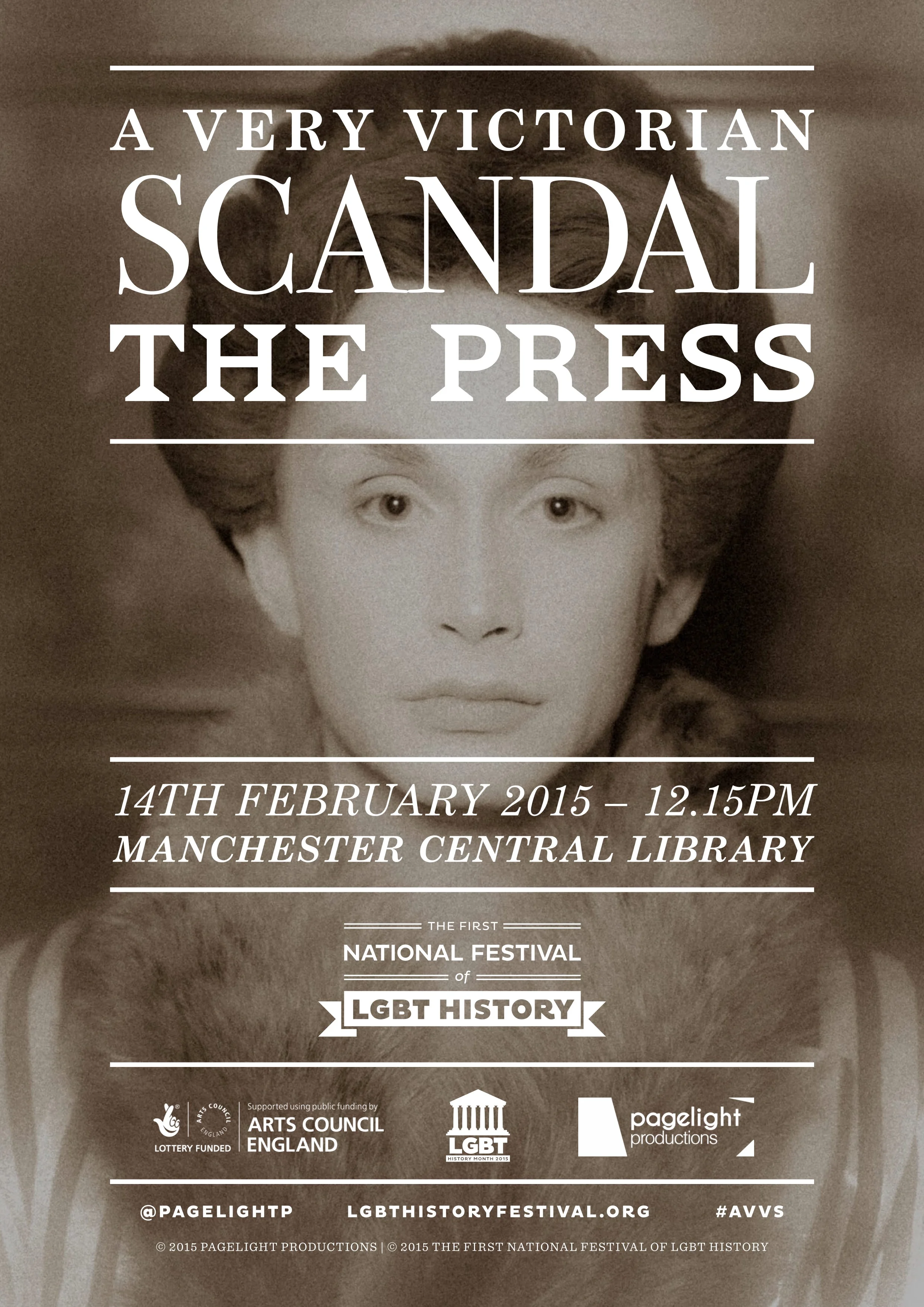

Jeff asked for a meeting to discuss an idea he’d had. 2015 was going to be the tenth birthday of LGBT History Month. The popularity of the month had grown and grown, and whilst there had been incredible take-up, there was also a plateau in event attendance. In addition to a month of grassroots historical and political activity, LGBT HM wanted to create a city-based weekend festival of history for the tenth anniversary. Jeff wanted to include a full dramatisation as part of the programme, something headline-catching and full of strong optics for social media and press.

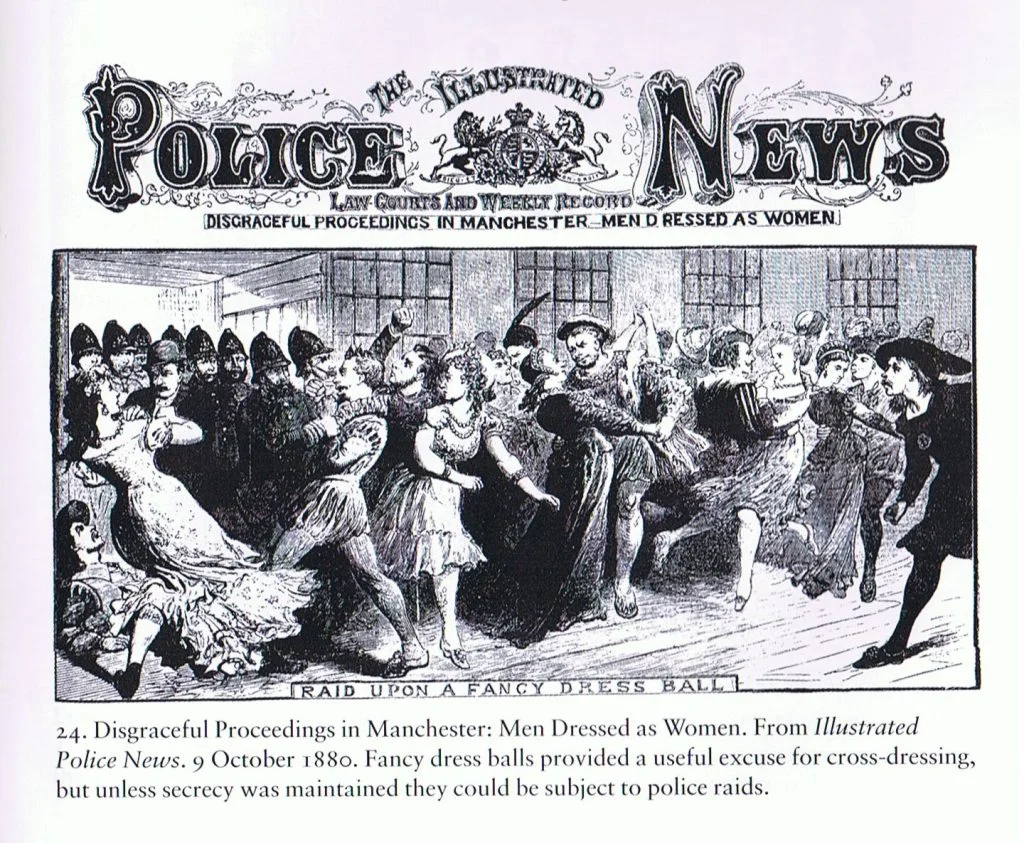

Jeff was completing a PhD in “The criminal prosecution of inter-male sex 1850-1970: a Lancashire case study”. Not all good historians recognise a good story when they come across one, but Jeff does. He’d catalogued the press accounts of a large police raid on an all-male drag party in Hulme in Manchester 24th September 1880, and the collapse of the subsequent trial of the men arrested. And the raid attracted a lot of reporting, stretching across the Manchester and Salford press to the North West, into Yorkshire and then nationally, into illustrated weekend editions and even into the American press. The Court papers in relation to the trial no longer exist, but Jeff had cross referenced each of the men arrested to the nearest census data before and after the trial. This provided a rich picture of the careers, social status and domestic circumstances of the 47 men who went to trial. And what a story it was! There was a blind accordion player, a man dressed as a nun on the door, a lustful night of ribald songs and dancing in a Temperance Hall, a secret society of men who booked spaces under the pseudonym of the Assistant Pawnbrokers of Manchester, a police raid by a detective who was the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, and the curious collapse of the trial at the moment a new Chief Constable came to power in Manchester. There was almost too much material and certainly too many different stories. It was an embarrassment of riches.

Our solution was to trim back the 47 men to a core of four contrasting men and a wider cast of twelve additional characters, and then to shape three separate short plays out the material. We put the whole project under the umbrella title of A Very Victorian Scandal and then had sub-title for each piece: The Raid, The Press and The Trial. By having three separate but inter-connected narratives, we could dramatise the different elements of Jeff’s research without them all having to fit together neatly into one full-length play. One character In The Press was invented, a journalist called Henry Newman. He acted as the embodiment of the relationship between the Manchester Police and the newspaper establishment. I made him the reporter charged with accompanying Caminada on the raid of the drag ball, only to see his lover arrested. He acted as some narrative glue to tie together otherwise disparate elements of the researched history.

Having staged something that involved sixteen characters, in full period costume, performing three different plays, in three different non-theatre spaces, over three consecutive days, we decided to make life a little easier for ourselves in 2016. I commissioned Abi Hynes to write a play based on the life of Henry Stokes, which Abi will tell you about shortly. Once Abi had agreed to the job, she quite reasonably asked, “So, what is festival theatre? How do I do it? How is it different to just writing a play set in the past?” I think there are three things that make festival theatre distinct:

- It’s based on original historical research and the writer works with a historical adviser throughout the script development process. We are not aiming for historical accuracy per se, which anyway could be argued to be impossible and a fool’s errand. We are aiming at literacy, i.e. that whatever creative choices the writer is making, they are coming at it from an informed position. Put more simply: they’ve done their homework.

- Its not about simply attempting a recreation of events in a naturalistic performance and documentary writing style. We are interested in essences, and in equivalences, way of communicating the core of something to a contemporary audience, what Professor Sanders calls “learning from the heart.”

- Our focus is on the voice of ordinary working-class people. We are not telling the stories of a privileged, creative, London-based elite. Our focus is on how people like us made sense of the world’s they lived in and the rules, laws and regimes they found themselves working with, or limited by, or resisting against. So, with some sort of explanation as what was expected, I handed over to Abi.

ABI: The story of Mister Stokes: The Man-Woman of Manchester goes like this. A man was walking his dog by the River Irwell in Salford, 1859, when he saw a ‘tall hat’ floating on the top of the water, and discovered that a man had fallen into the river and drowned. That man was Harry Stokes – a local bricksetter and special police constable, who owned several alehouses in the area with his second wife, Francis. It was only when the body was pulled out, and examined under instruction by the coroner, that he was found to be biologically female.

That’s the story as we, the writer and producers of the play, got used to telling it. The key challenge that Abi Hynes, the playwright, faced was how to dramatise Harry Stokes’ story when the inciting incident was the death of the central character. To solve this problem, and to allow Harry Stokes to tell his own story from beyond the grave, she invented Ada. There would have been two women who laid out Harry’s body and discovered his secret – I condensed these into one woman, who encounters Harry’s ghost and gets to hear about chapters of his life first hand. By adding this fictional element to the drama, she was able to find a vehicle for the truth (or at least our interpretation of it).

STEPHEN: 2017 was a big years for LGBT HM. Marking the 50th anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act 1967 saw a wave of activity across the year: museum exhibitions, art exhibitions, documentaries, television seasons…it felt like every other major cultural institution engaged with the anniversary in some way. But how was LGBT HM itself going to mark the anniversary? The answer, and it seems an unlikely answer, was with two plays about Burnley: The Burnley Buggers’ Ball which I wrote and Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator, which Abi wrote.

A few years earlier, Paul Fairweather, a long-standing activist and historian, got some funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund to create an LGBT Heritage Trail for Burnley. I asked Paul to take me on it, which he generously did. LGBT HM had already identified a potential story: on 30th July 1971 the first ever attempt to open an LGBT Centre, an Esquire Club in the language of the time, ended with an electric public meeting in the Burnley Central Library. The very room that the meeting was held in still exists, albeit in a moth-balled part of the library, and as soon as I set foot in the room, I knew we had to tell this story. I didn’t know that within a couple of hundred yards of that room, another forgotten part of LGBT history had occurred in 1978, which Abi will talk to you about shortly, and which became the second piece for 2017.

Initially inspired, I did my research but all I really had for a plot was: some men arrive; some men give speeches at one end of a room; everyone goes home. It wasn’t the most riveting plot. And then there was a moment of serendipity. I was working on another project at the People’s History Museum and through that, my path crossed with Michael Steed. As far as we know, Michael is the last living person who spoke at the meeting. And Michael was willing to go out to dinner and be interviewed by me.

In the meeting itself, there was a crucial moment when a speaker from the GLF takes over from the organisers. He shouts down the hecklers and shuts up my panel of speakers. He says, “Were speaking as if there are two gay men in this room and five in the whole of Lancashire. I want every gay man in this room to stand.” According to the published account of the meeting in Peter Scott-Presland’s Amiable Warriors, somewhere between a half and two thirds of the room stood. The panel: Michael, Ray Gosling and LGBT hero Allan Horsfall all stood. At dinner, Michael first gave a conventional retelling of this account. Then after another glass of wine, he leant forward, placed his hand on my forearm and made his revelation about the panel. He said, “Of course, the truth is that none of us stood. Not one.” “So, Allan Horsfall the brave, out campaigner, the grandfather of LGBT right in the UK, than man more responsible than anyone for getting the 1967 Act passed, that Allan, didn’t stand?” I asked again, needing confirmation. “No”, came the emphatic answer from Michael.

Up until then, I thought I’d been writing a piece loosely about Ray Gosling chairing a meeting. Suddenly, I had a different, much more compelling story, a story that turned the history of that meeting on its head. Alan was now the main character and the play was about him not standing. I would send him back through time to try again, to make a deathbed bargain with an angel to try to change something in his past.

ABI: Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator told the story of Mary Winter, who was sacked from her job as bus driver in Burnley for refusing to take off her ‘lesbian liberation’ badge. In her ultimately unsuccessful fight to be reinstated, she staged a demonstration outside Burnley bus station, and achieved national press attention by recruiting Vanessa Redgrave to publicly support her campaign. Once it was all over, however, the history of Mary Winter we’d found in our research came to an abrupt halt. It seemed that she had left Burnley, but there was no further trace of her – which gave a firm end point to the play beyond which we weren’t able to speculate.

It was only when we started promoting the Burnley Plays that we were able to pick up the trail again. After we were interviewed about the plays in newspapers and on the radio, we were contacted by two separate people who told us they’d known Mary Winter later in her life. The first knew her when she was living somewhere else, under a different name. The second told us about an archive held by Feminist Archive North in Leeds, which contained a lot of press cuttings and other materials from Mary Winter’s protest in Burnley, amongst a lot of other documents, and had been donated by somebody going by this same new name. For the first time, we were able to identify the donor as Mary Winter herself – and Abi and our historical advisor Paul Fairweather went to visit the archive and trace some her activities after Burnley, which included other social justice campaigns across the country.

We have never managed to contact Mary herself – though not through want of trying. We feel that we have a duty to respect her privacy – it’s possible that she doesn’t want to be found, and that her history, though important and fascinating to us, may not be something she now wants to be publicly associated with. But it was thrilling to discover this new evidence about other chapters of her remarkable life.

STEPHEN: Abi’s experience with researching Mary Winter illustrates one of the dilemmas facing us. We might value and want to dramatise and to celebrate someone’s lived experience, but what if they don’t? As a writer, the research process is primarily about creating a story, not necessarily about creating a cautious provisional version of a truth about the past. The rules of what makes good drama and what makes good history may overlap, but they aren’t the same thing.

In making a popular drama out of someone else’s research, there is a kind of narrative hierarchy that the drama then gains over the research. Specifically because drama is emotionally engaging, it is remembered vividly. There are pictures of the play, a mass of articles about the production and even films that can reconstitute the dramatised version of the past endlessly to audiences potentially all over the world. That gives the drama a kind of weight and authority that the original historical material may lack. The drama itself may contain all manner inventions, conflations and simplifications, and yet the danger is that it might itself become more widely known historical account.

The dilemmas are different with every project we undertake and we are learning and changing and refining as we go, ever more conscious of the power of the story-telling we bring to our audiences.

Directing Heritage Theatre: Helen Parry

Helen Parry has directed four pieces of Festival Theatre and explores the joys and challenges of the work in the context of her wider career.

I’ve been involved for the last three years with LGBT HM, directing four very different pieces of work. I have had previous experience of site specific work (Styal Mill in Cheshire, Farfield Mill in Sedbergh, and at the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry) and thought I was prepared for the challenges!

The first project in 2015 was “A Very Victorian Scandal”, designed as three pieces which would take place in three venues over three days. They comprised of dramatized scenes (of which I directed two) and a “ball” which was staged at Via on Canal Street and directed by Dan Jarvis. The logistics of moving actors, costumes, props etc. from space to space took some planning and there was the ever present worry that things would get lost in the process.

The major headache was not being able to have much rehearsal in the actual venues but trying to visualise how the pieces would look in situ. This project also had a musical director and a choreographer which meant splitting rehearsal time between us and scheduling carefully so that all elements of the work were sufficiently developed. Another issue was how to “control” our audience and how to pull their focus to where we wanted them to look at various moments in the drama and to move them about if necessary.

2016’s production of “Mr Stokes: The Man-Woman of Manchester” was a much simpler affair involving, as it did, only two actors. This was very sensitive material and we were lucky to secure a male trans performer, Joey Hateley who brought tremendous insight and skill into the work and who was very open and eloquent in rehearsals, thus enabling his fellow actor to develop her varied roles in relationship to his one of Mr Stokes.

2017 saw us embarking on a much more contemporary tale within The Burnley Project. Here I only had responsibility for one element of the whole piece, “Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator”, working with three women who were also taking part in the larger companion drama, “The Burnley Buggers’ Ball”. The main venue, Burnley Library, meant bringing our audience up a staircase and then asking them to face one way for the first play and to turn around for the second. We also marched them out of the building at the end as if they were part of the original demonstration the play was based on!

The writers involved ; Stephen M Hornbyand Ric Brady in 2015 and Abi Hynes and Stephen M Hornby in 2016 and 2017 respectively, were in regular communication with me in the early stages of writing the pieces, attended some rehearsals and were as open to feedback from the company as we were to theirs. There was the ever present concern that these were not fictional characters but were based on real people and events and it was our duty to present them and the issues involved as honestly and accurately as we could within the framework of a theatrical performance. We shared research sources and visited the various venues to take photographs and debate the staging logistics. The stage managers input were essential here as theirs was the overall control during the actual performances.

For me the most compelling part of the projects has been taking the dramas out of theatre buildings into new spaces and having the audiences in and amongst the players. In each instance the atmosphere has been tremendous and the audience feedback after each show has been so rewarding. The different settings have complimented and enhanced the material on show and added another dimension to the presentations. The absence of stage lighting, sophisticated set design and soundscapes has meant the writing and acting are very exposed and this felt both risky and exciting. Our responsibility for the storytelling becomes greater under these circumstances.

I have felt very privileged to be part of the creation of these “hidden histories” and have learnt so much from the experience. It has opened me up to the possibilities of the thousands of such stories that must be out there, waiting to be discovered.

Photo credits: Nicolas Chinardet

Directing Heritage Theatre: Raiding A Drag Ball

Dan Jarvis directed the very first episode of the first piece of Festival Theatre, “A Very Victorian Scandal: The Raid.” It was a complex immersive period recreation of a drag ball, with live music hall singing, a chorus of can-can boys, a nun on the door and a live police raid. Here Dan considers the many and varied potentials for all not being all right on the night.

It was a privilege to be invited to work with director Helen Parry and writers Stephen M. Hornby and Ric Brady on the LGBT History Month production of ‘A Very Victorian Scandal’.

As a subject matter it was fascinating to me – a chance to lift the lid on the stories and communities that have been neglected by history. What made the story of the Hulme Drag Ball raid of 1880so engaging was that it reveals to us early formations of the LGBT community safe spaces and counter-publics that we now celebrate in areas such as Manchester’s Canal Street, Brighton and Soho. Unearthing these real life stories gives our community a sense of heritage, history, legacy and legitimacy.

When the project evolved to incorporate a recreation of the ball itself (before the subsequent trial and backroom political drama), it was a pleasure to use and combine my experience in directing musical theatre and postgraduate research in subcultural queer cabaret and theatre to create something really unique.

Performing in a public space not designed for stage performance offered a wealth of challenges but also opportunities. Logistically VIA is a tricky space to work with. The bar’s unique design throws up a multitude of issues surrounding sightlines and levels and blurred boundaries between audience and performers. Then there’s the issue of how do you ensure your actors are heard in an open bar on a Friday night? The biggest risk however was how the work would be received by the incidental audiences: punters who were there to enjoy a bar they frequent and feel their own sense of ownership over. There was every risk of heckling, disruption and a lack of the theatre etiquette we are used to in conventional performance spaces.

However, I would make the counter-argument that it was taking this risk which was the performance’s greatest strength. We were able to take theatre to an organic audience comprised of LGBT History Month delegates, friends and family and an incidental LGBT bar audience.

In a piece that celebrates the heritage of LGBT community spaces, it felt integral to the project that we continue to engage those who inhabit such spaces today. Whether they choose to directly observe and follow the performance and the individual characters and storylines, or whether they just absorb the atmosphere and join in a well-known chorus or two – the connection and engagement with these non-theatre goers was vital.

In terms of repertoire we took a slightly anachronistic approach using subversive music hall and cabaret numbers from throughout the history of the genre, ranging from queering classic pre-war songs such as “Hold Your Hand Out Naughty Boy” to paying homage to the likes of Danny La Rue and Hinge & Bracket. The result was a warmly nostalgic, rambunctious road-trip down a treasured piece of our history.

The mixed programme of lesser-known music hall numbers and well-known rousing songs in which the audience were encouraged to participate helped construct a lively and inclusive performance alive with a community spirit.

It was a pleasure to work with the ‘A Very Victorian Scandal’ team and to help recreate a truly sensational moment in Manchester’s hidden histories.

All photo credits to Nicolas Chinardet.

Writing Heritage Theatre: “The Burnley Buggers’ Ball”

Stephen M Hornby, our National Playwright in Residence, looks back at writing “The Burnley Buggers’ Ball”, one of two pieces commissioned to make the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.

I thought I was writing a play mostly about Ray Gosling, the famous broadcaster from the 1970s. Jeff Evans and I had been discussing what to do to mark the 50th. Jeff had found the forgotten story of the first attempt to open an LGBT centre in the UK. It was a struggle that began with the 1967 Act and came to fruition in an East Lancashire mill town at the beginning of the 1970s. As everyone kept saying to me throughout the project, “Who knew?”

Ray Gosling chaired a meeting entitled ‘Homosexuals & Civil Liberty’ in Burnley Central Library on 30th July 1971 at 8pm. The local press commented on how well he chaired a confrontational meeting at which the atmosphere was described as ‘electric’. This meeting is now becoming reassessed as the birth of the civil rights movement for gay men in Britain, the moment the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) and Gay Liberation Front (GLF) came together; the moment of transition from reasoned debate to civil rights demand which literally occurs in the meeting. As Ray was the chair of the meeting, and a well known figure, it seemed reasonable to research him first as the starting point for writing the play.

Dramatising something that is in living memory was new ground for LGBT History Month. I could talk to people who remember the meeting, people who were at the meeting even. I couldn’t speak to Ray though. But there is a wonderful legacy to draw from, the documentaries, the radio programmes and his very own archive at Nottingham Trent University. Copies of Ray’s papers in relation to the meeting and his diary for the period were kindly provided by the archive, perused and duly considered. One of the actors I work with regularly met Ray. She was a big fan of his work and when she approached him and was unable to focus her appreciation into specific memories of a specific programmes, was witheringly dismissed by Ray in a textbook example of how not to respond to a tongue-tied fan.

After many hours listening to him present material, I have to say, of varied quality, I was struck by several things, conclusions that underpin the characterisation of the Ray that I wanted to write. He was very principled and cared about ordinary people. He didn’t suffer fools at all and always thought he knew best, even when he palpably didn’t. He was a bit of a blagger and a lot of a visionary. He probably wasn’t very easy to like, but he would be someone you respected, someone who would teach you valuable life lessons, someone you would always remember. His judgment may have been off sometimes and he may have drunk too much, but there was a fire, a kind of nobility and a strong instinct for what’s important in life and what’s at the core of people.

I knew Ray worked closely with Allan Horsfall, who was also at the meeting in Burnley but didn’t speak. Allan is the grandfather of LGBT rights in the UK. Allan’s silence at the meeting was problematic. How could I stay true to his silence, but also honour a man who was so important in making the 1967 partial decriminalisation happen? There’s also less of Allan, in terms of archive. The recordings and films of him that do exist show someone who is self-conscious and only gives clues to the man within. At this point in my research, I felt a bit despondent. I knew a lot about Ray’s character and a bit about Allan’s, but essentially, all I had was four men sat on a podium talking for an hour in a stuffy room in Burnley. It wasn’t the most promising premise for a dramatisation.

The something wonderfully serendipitous happened. I was working on another project and by chance met Michael Steed. Michael is, as far as we know, the only person living who spoke from the platform at the meeting. He kindly agreed to being interviewed over dinner and replayed an account of the meeting I had read before. My historical adviser on the project was Peter Scott-Presland, the author of the wonderful book “Amiable Warriors”, a multi-volume on-going record of the history of CHE. He had interviewed Michael, amongst many others, about the meeting and Michael gave pretty much the same account as he was giving me over dinner. There was a pivotal moment when the GLF somehow took over and threw away the procedural order of the CHE, zapping the meeting. Accounts of exactly what happened vary. Some say Andrew Lumsden from the GLF zapped the meeting, some say Ray picked up on what Andrew had said and that it was him who zapped the meeting. Whoever it was, the meeting was zapped:

“We are speaking as if there are no homosexuals in this room and only five in the whole of Lancashire. I want everyone who is gay to stand up. Stand up now if you’re gay.”

So went the zap…roughly. Again accounts vary but somewhere between one third and two thirds of the room stands. Peter’s account implies that, of course, all the platform speakers, Ray and Allan and Michael, all stood. A couple of glasses of wine into dinner, Michael suddenly seizes my arm and with a look of deepest sincerity says one devastating line, “Of course, the truth is none of us stood; no one on the platform stood.” How could the brave, pioneering, ceaselessly campaigning Allan Horsfall not have stood? History just changed.

To me as a writer, the moments when people behave in unexpected ways are always the most interesting. I would’ve assumed that Allan would have stood, but here was an eye witness, a man who was on the panel with him at the meeting, telling me he didn’t. There was my play. There was the way in to the material. The central question of the piece became: why didn’t Allan Horsfall come out when called upon to do so? And suddenly the play was about Allan and not about Ray.

Though the accounts of the meeting are contested, if Michael’s account is accurate, then we have a profound new insight into the events of 30th July 1971. And the process of writing a historical play has disrupted the published historical version of events. Dramatising history can change history and turn upon a few words in one sentence.

All other photo credits: Nicolas Chinardet

Writing Heritage Theare: “Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator”

Abi Hynes looks back on the process on writing “Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator”, one of two pieces of Festival Theatre for 2017 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act 2017.

I was pretty daunted by the prospect of writing a play set in the recent past. Burnley in the 1970s might as well have been Tudor England to me; I wasn’t born yet, I had no memories of that decade to draw on, but I knew that a high percentage of our audience would remember it well, and have a keen eye for any mistakes.

In the first phase of my research – steered by my wonderful historical adviser, Paul Fairweather – I became fascinated by the story of Mary Winter. In 1978, she was fired from her job as a bus driver for wearing a ‘Lesbian Liberation’ badge, and she took on the bus company and the local press (garnering high profile support from Vanessa Redgrave and staging a demo outside Burnley Bus Station) in her campaign to be reinstated. But what could I bring to a play about this era of gender and LGBT politics, not having lived through it?

My first breakthrough came from a conversation with my brilliant director, Helen Parry. She told me the story of when, as a single working mum in the 1970s, she found that she wasn’t allowed to rent a television without a man to sign for it. It gave me an insight into the frustrating and humiliating restrictions that were still being placed on women at that time, and I began to find my feet with the script I wanted to write.

As the project developed, I realised that recent history is exciting because it’s not over yet. The next breakthrough came when, in response to the publicity we were doing for Burnley’s Lesbian Liberator, people started to come forward with more information. We hadn’t found any trace of Mary Winter or what happened to her after the demonstration failed to persuade the bus company to let her return to work with the badge still on. We believed she had left Burnley, but that was all we knew. Our new sources helped us to work out that she had later lived in several other places under a different name, and been an activist for many different causes. With this new name (having never managed to find her and get in touch myself, I won’t reveal it here), we were able to discover the letters, press clippings and poems she donated to Feminist Archive North in Leeds, and our visit there revealed enough material for a whole new play based on what she achieved in her life after Burnley.

After each performance, we met audience members eager to share their own experiences of being LGBT in Burnley, and so our stories grew. A highlight for me was when a much younger audience member commented that the Burnley Plays had made him feel proud of and connected to the place he had grown up in for the first time.

The best lesson that writing two plays for LGBT History Month has taught me is that participating in history is an active and collaborative thing. And so it should be. That’s the joy of the festival: it connects our past, our present, and our future. By telling these forgotten stories, we don’t just remember history – we make our own.

Writing Heritage Theatre: “Mister Stokes: The Man-Woman of Manchester”

Abi Hynes looks back on writing her festival theatre play for 2016 “Mister Stokes: The Man-Woman of Manchester”

I realised pretty early on that writing a play about Harry Stokes was going to involve summoning his ghost. It was one of those ‘click’ moments – it’s like looking at the picture on the box of a 1,000 piece jigsaw, and suddenly the pieces in from of you become a puzzle that can be put together, rather than just a baffling jumble of shapes. I think the reason I’m drawn to research and historical plays is that puzzle-like quality, which often feels more like codebreaking than creating. I always tell myself that there is a way to solve the problems that the piece in front of me poses, and I will find it, if I just give it enough time and thought.

This is mostly just a useful mental trick to take the pressure off while I’m writing; because, of course, you have to invent things. Research provides us with the facts but the facts are not a story, and a story is what an audience needs. That human touch that opens the door and lets the truth in; blurry and subjective and contradictory as it may be (and usually is).

Mister Stokes: The Man-Woman of Manchester told the story of a Victorian Manchester and Salford bricksetter, who drowned in the River Irwell and was discovered to be biologically female. The ‘story framework’ I invented for the play about him grew from two key concerns. The first was that I wanted Harry – or my imagined version of him, anyway – to be able to tell his own story. The second was his mysterious drowning, which really was the ‘inciting incident’ from a playwriting perspective, in that his exposure, and our resulting contemporary interest in him as a potential trans pioneer, all sprang from that event – regardless of the fact that it left me with the dilemma of my main character being dead right at the start of the play.

My solution was to create a situation in which Ada, a (fictional) woman brought in for the ‘laying out’ of Stokes’ body, encounters his ghost. In the course of their strange meeting, Harry not only tells Ada parts of his life story, but also shows her, by transforming her into both of the (real) women he was married to and getting her to help him re-enact scenes from his past. It gave the play its own dramatic arc; the audience get to invest in the growing friendship between Harry and Ada as his candor overcomes her prejudices, and ultimately, when his ghost has left her, we also witness her betray him by revealing the anatomical truth.

Naturally, none of these scenes with Ada really happened. I mean, there really were two women who would have examined Harry Stokes’ body before the inquest, but I doubt that either of them were much like my Ada, and I am certain that neither of them had a conversation with his ghost. But the story that the framework allowed me to tell about Harry’s life was, at the very least, entirely based on research, and represented a possibleversion of what happened, which is often the best that a historian can hope for. Ada held the door open, and with any luck some truth crept in.

Photo credit: Nicolas Chinardet

Writing Heritage Theatre: “Devils in Human Shape”

Tom Marshman looks back on the process of researching and writing his 2016 LGBT History Month Festival Theatre piece, “Devils in Human Shape”.

The project started with a day trip to Bristol Records Office by the lead artist Tom Marshman and the historical adviser Steve Poole. Together they looked at old court records of sodomy cases in the 18thCentury. Tom found some documents that he wanted to transform into theatre and took photographs of these. Steve then deciphered the font, and typed them out so that they were workable and understandable for using in the studio to devise from.

The development of the work took place over three weeks, with Tom developing material over two weeks and then bringing it into a further one-week development phase at The Trinity Centre, Bristol. This involved lead artist Tom Marshman, historian Steve Poole, and two additional performers; Danny Prosser and Rachael Clerk. The week’s work ended in an informal audience work-in-progress sharing. The piece relied heavily on engaging the audience, so we used this sharing to test how audiences responded to the work and it’s moments of intimacy. This was very important in shaping the final piece.

During the development week itself, the performers first met and read the texts sourced by Steve and Tom. They talked about how best to convey these documents and what kind of overall message they wanted to convey with the work. At the beginning of the process we had to find a way to use these legal documents, some of which were very hard to decipher, but as we progressed in our understanding we noted that a sense of dramatic story wasn’t strongly present in the sourced texts. We felt it was our job to develop characters who could show these stories and hold a “malignant presence”, embodying public views in the 18th century, in the piece.

A lot of the text was written without any sense of emotion, or any strong viewpoint either judgemental or sympathetic. We were looking for a love story within the text but due to the formal documentation we couldn’t find one. Through further research, we noted an account of two sodomites who “embraced very affectionately” before being hung and chose to dramatise this story and position it at the end of the piece. After studying all these accounts we could see how complex and hard it must have been for these men. We wanted to juxtapose these stories with a modern account of a “hook up” that was mundane, casual and shared in a non-sensationalist way to highlight the difference between modern LGBT culture in society and that in the 18th Century.

The creative team worked alongside costume designer, Neil Stoodley, who costumed the piece, and created incredible large, black hats draped with lace, which made a ‘canopy’ around the wearer’s head. The hats were used as a strong choreographic tool within the performance piece and were very effective in creating intimate, gossip-like encounters with audience members.

Throughout the development of the work, Tom Marshman was the lead artist making directorial decisions with input from the two other performers, Danny Prosser and Rachel Clerk. This was the first time that Tom took on a role as a director.

Steve Poole also came into the creation period for an afternoon, which proved very important, as there were a few corrections that needed to be made to be historically accurate and it supported the other two performers to understand the historical perspective on the documents being used.

There were three performances of “DiHS” as part of LGBT History Month in 2016 at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the University Centre, Shrewsbury and at M-Shed, Bristol. The piece also had an afterlife in 2017, with performances at Aberystwyth Arts Centre, The Watershed, Bristol, Dartington Arts, Totnes, and the V&A again at one their late nights openings.

All of the shows were very well received and attended, and there have been invitations to work with a sound artist to make a recoding of the work which would be broadcast on local radio, extending the legacy of the piece.

Writing Heritage Theatre: “A Very Victorian Scandal: The Press”

Stephen M Hornby looks back on writing “A Very Victorian Scandal: The Press”, the second in a trilogy of plays dramatising the Police raid on an all-male drag ball in Manchester in 1880.

There were several elements to the puzzle: an ambitious man who wanted to become Chief Constable, an unprecedented press frenzy that spread across the world and a trial that never was. I was working through the papers that Jeff Evans, my historical adviser, had given me in search of a smoking gun, something to link all of these events together, beyond circumstance and suspicion.

In between the raid on the drag ball and the trial of the 47 men arrested a few days later, Chief Constable Pallin was replaced by Acting Chief Constable Wood (a man as keen on policing morality as he was on policing the streets). The story of the raid went from being covered by the local newspapers, to regionals, and on to nationals, with several illustrated special weekend editions covering the events, and eventually on to the American press. It was a sensation. Yet, when the men came to trial, no criminal charges were ever brought. They were bound over for a surety which some could pay and others could not, landing them in prison. In a sense, this was the real scandal of the whole episode. There had to be a smoking gun somewhere

I read the self-penned memoirs of the detective who led the raid, Jerome Caminada. The case was easily the biggest of his career in terms of press coverage it brought him. Despite two lengthy volumes of memoirs, some detailing relatively minor crimes, Caminada never mentions it once. Nor did he ever speak publicly about the case, despite retiring from the Police into a life in local politics. Was he deliberately choosing to remain silent about the love that dared not speak its name on moral grounds (he was a committed Catholic)?

But then Caminada mentions, in some detail, other forms of sexual offending in his memoir and all kinds of (as he would see it) illegal and deviant behaviour. Was he perhaps ashamed of his role in some way? Had there been some connection between Caminada’s well-timed raid and the appointment of a new Chief Constable wanting to be known for his tough policing of sexual morality? The Manchester City Police had been informed of a similar ball some years earlier, but had taken no action. Was the imperative to act now being driven by an Acting Chief Constable keen to prove himself to a Watch Committee who wanted a crackdown on any perception of Manchester as a city of vice?

If that was the case, and I had nothing yet to prove it was, then it was a monumental failure. The local press reporting of the raid could perhaps be relied upon. There is evidence of formal and informal connections between police forces and journalists at every level in the system. But the unexpected thing was the expediential growth in interest in the story.

I could imagine a Watch Committee that was pleased with a headline the day after the raid showing that Manchester showed no tolerance for men behaving indecently with each other. I could also readily imagine their horror when the story spread and spread, associating Manchester and unnatural vices for day after day after day across the North, then across England, then across the world. And their dread at anticipating the appearance of 47 men at Magistrates Court only to be remitted to Crown Court for lengthy trials which might mean the story went on for months and months. Was this why the case collapsed at Magistrates Court on the first and only hearing?

he raid had been a large and expensive and very public Police operation. There was the sworn evidence not just of the respected Caminada, but of other constables, all attesting to the depravity of the ball. But, in the end, no criminal charges were laid and the men were bound over. It was extraordinary. Had the Watch Committee now desperately tried to end the prosecution before any embarrassing trials could begin, which might mean detailed testimonies and a painfully prolonging of the scandal?

As I started writing, I had some key facts around the replacement of one Chief Constable with another, about a press appetite for the story that no one could control, about Caminada’s mysterious silence and about the perplexing puzzle of the trials that never were. I may not have the smoking gun, but I certainly had the bullets it has been loaded with.

I choose to use Caminada and Wood as two of the three characters in the piece and play out the tensions of over the trial, Wood’s promotion and the control of the press between them. But I needed some way to bind those stories together and bring them into the action on stage in each scene. A journalist was the obvious choice for a third character. I invented Henry Newman as the embodiment of the new journalism that was emerging during the period, and made him the person who Caminada uses to first leak the raid story too. Newman, of course, had to be secretly homosexual. He is then faced with either printing the story of a lifetime and betraying people he knows, or not printing the story and potentially outing himself. This formed the basis of the first draft of “AVVS: The Press”.

The dramatist in me wanted to make the stakes for Newman even higher. I knew from the research that one of the men arrested, Ernest Parkinson, worked as a minstrel. What if Ernest was a female impersonator, Newman’s secret lover, and unbeknownst to Newman was at the ball? Now there were two biographical characters, one invented character and one character based on a real person, but with some invented biography.

I had a story that was three parts fact, two parts informed speculation and one part pure invention. That felt like the right balance to illuminate the issues of the police relationship with the press, whilst also conveying the story in a 30 minute piece with four actors in a library on a Saturday afternoon on St. Valentine ’s Day.

Photo credits: Nicolas Chinardet (except for poster image)

Writing Heritage Theatre: “A Very Victorian Scandal: The Trial”

Ric Brady looks back on writing “The Trial”, part of a trilogy of plays that formed the first programme of Festival Theatre in 2015.

‘The Trial’ was the final piece in ‘A Very Victorian Scandal’: three theatrical pieces that were performed over the first National Festival of LGBT History in 2015. ‘The Trial’ was a retelling of the Hulme Fancy Dress Ball of 1880, based upon the research of Jeff Evans.

The Hulme Ball Raid was the biggest police raid in British history. It ended in extraordinary scenes at the Manchester Police court, which were written about in newspapers across the world. Distilling this huge event into a thirty-minute retelling threw up some challenges that, as a writer, I had to face.

Following the research: When I began writing ‘The Trial’, I wanted to tell a story about the police’s abuse of power. The forty-seven men arrested at the Hulme Ball had not been charged with a crime. Yet, they faced large fines (two-thirds of the average annual salary) and had their reputations destroyed in the press.

However, after researching everyone involved in the raid, the police, legal system and the forty-seven men, I came to realise that the truth wasn’t that clear cut. Everyone involved had their own motivations, and some of the police and prosecutors were doing what they believed in, no matter how abhorrent these beliefs were to a 21st century gay man.

This helped me to realise that, to dramatize past events, I had to follow the research to find the story, rather than pick research to match a pre-planned one. While the end piece still slanted towards empathy for the forty-seven men, it was more balanced than I had originally intended it to be.

Choosing Characters: The hardest aspect was to reduce forty-seven protagonists to a handful that could be focused on in thirty minutes. Thanks to Jeff Evans’ research, which included census records, I found four characters who I felt both a connection to and whose history could be traced. Unfortunately, Jeff’s research didn’t give me enough information to write detailed backstories for these characters. I felt uncomfortable allowing my imagination to create whatever it wanted. These were real people I was writing about. Instead, I allowed other research about the period to inspire my imagination.

Making it relevant: As fascinating as I found the newspaper accounts from 1880, I had to face the fact that a modern day audience might not find them as interesting. I wanted the audience to be moved by the piece, and to do this, I tried to make the protagonists as authentic as possible. Each had their own backstories, each had something at stake. The four characters were used throughout the three pieces, with Parkinson, and his alter-ego Kitty, being a strong presence in all three.

Production changes: Things can change once production starts. The venue that we had originally wanted to use for ‘The Trial’ became unavailable during the writing process. I changed some of the immersive theatre elements to fit the new locale. After seeing the first draft, the cast and director weren’t keen on the immersive theatre elements, because they felt they wouldn’t fit within the new venue. I accepted their feedback, and in the final draft, the immersive elements were reduced.

The positive audience feedback made me feel that I had succeeded in facing these challenges. I managed to streamline the legal proceedings so that the audience could follow them, while remaining faithful to the events. I also managed to highlight the fear and despair that the men would have felt by telling an engaging story.

I think having more stage-time, plus the ability to perform scenes in different settings, would have made my life as a writer easier. Nonetheless, it was a joy and a privilege to tell this story, and to be a part of “A Very Victorian Scandal”.

Arts Council of England supports LGBT History Month

We’re delighted to see this post from Arts Council England on 06 March 2017 about the national range of their support for LGBT History Month projects in 2017. Here’s an extract with a link to the full blog:

“February was LGBT History Month – 28 days dedicated to raising awareness about equality, promoting the benefits of diversity and helping to overcome prejudice through education.

The arts provide an incredible opportunity to break down barriers, promote understanding and change perceptions. So, inspired by Schools OUT UK’s LGBT History Month, we’ve pulled together some of the great LGBT projects that we support. From theatre productions and museums through to live art and spoken word, we fund an amazing range of projects that illustrate why our diversity is what makes us great.