By Ian Temple

Russell T. Davies’ new five-part series It’s A Sin on Channel 4 has floored me. Not only does it portray London in the early 1980s for a gay man so accurately (helped with a nostalgic soundtrack featuring Erasure, Bronski Beat, Culture Club, Wham, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Divine and Queen), but it uncannily brings to life a friend who died 26 years ago.

Dursley McLinden (May 1965 – August 1995 – loosely portrayed by Olly Alexander as Ritchie) was three years younger than me, and was intoxicating. I had just moved from Brighton, where I was at art college, to start a life in the hedonistic gay paradise that was London. Dursley had moved from the claustrophobic Isle of Mann and was already making a splash in the West End, playing Young Ben in Stephen Sondheim’s Follies.

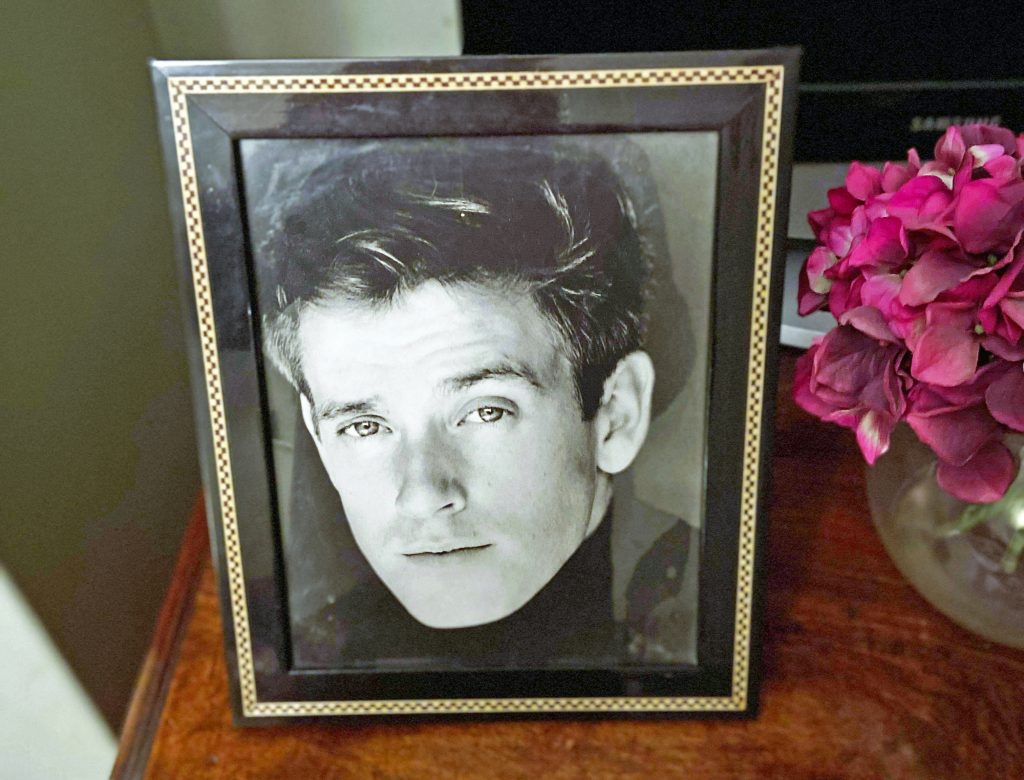

Dursley looked like the quintessential “juvenile lead” with his dazzling looks, dashing presence and flirtatious, winning charm. His vibrant circle of friends, who frequented the ‘Pink Palace’ (a flat rented by Jill Nalder and Dursley and shown in the series) quickly became my own. I met Peter Worthington, my partner for the next ten years, amongst this group.

The joys, and the boys, were plentiful. London was a riot of sex, celebration and youthful ambition and I embraced it. I was young, fit and attractive. We were supported by a group of older, established grand homosexuals who generously wined and dined us. Gay music artists were predominant in the charts, Pride marches were bigger and better than before, Heaven (London’s first mega gay club) had opened and provided a weekly, not to be missed, focus for our group.

Life was a big party. The pill had triggered a sexual revolution for the heterosexual community in the 1960s, so now after almost two decades since homosexual acts were partially legalised it seemed it was our turn.

The evocative soundtrack for It’s A Sin perfectly captures the joyous optimism of young gay men coming to London and coming out in record numbers. We did not have to hide our sexuality or live a life in the shadows. There was an explosion in the number of gay bars and clubs, with entrepreneurs such as a young Richard Branson spotting potentials of the ‘pink pound’.

Until then there were discrete venues you could go to, where you knocked surreptitiously on the door of an underground pub cellar for a latch to be pulled back, to be examined and let in. Being gay was like being in a secret club and it was fun.

There was club on Bond Street called the Embassy, opened in 1978 by a good friend of mine, Jeremy Norman. Jeremy aimed to provide Londoners with the kind of experience that the avant-guarde and the creative set were already enjoying in STUDIO 54 in New York.

Jeremy opened Heaven in 1979. I had heard rumour of it while I was still in Brighton at Art College. And as soon as I moved to London it became my epicentre.

Previously a roller-skating rink, the scale of this mega-disco was enormous. Two huge dance floors, exclusive VIP rooms, and endless corridors just made for kissing. The DJ Ian Levine created a distinctive high-energy sound.

I felt invincible and happy in my own skin. I remember making friends with James McClosky and Jon Cross (both now dead) and dance shirtless and carefree on a podium.

It was like being at a catwalk show of a major fashion house. The air was thick with the smell of cigarette smoke, sweat and poppers. Those in fabulous drag danced alongside beautiful boys in tiny shorts and, of course, we wore the obligatory ‘clone’ check shirt and back pocket hanky in our jeans. There was an elaborate hanky code to signal what you would like sexually. Gays could be themselves, hold hands, kiss their boyfriend, or, more often than not, other people’s boyfriends. Sex was high on the agenda.

Thursday was a must at Heaven, the start of a hectic weekend. I remember trying to catch up on sleep in the office toilets. At the time, I was working for Virgin Films, which was located next to Virgin HQ in Ladbroke Grove. Boy George, Annie Lennox, Marc Almond, Depeche Mode, and Heaven 17 were frequent visitors. Richard Branson has just bought Heaven from Jeremy and I had a free VIP pass and felt I had access to heaven on earth.

We were that group of gay men trying to follow their dreams, just as the shadow of AIDS was beginning to darken our bright young existence.

It began with rumours about a cancer in America that appeared to be targeting gay people. Nobody knew what it was, what caused it, or whether it was even real. Different people had different knowledge.

It is hard, in an era of excess information, to grasp just how difficult it was to find out anything concrete about a mysterious but deadly illness that was beginning to ravage an entire community. A virus that seems to infect only gay men? Ludicrous. We were warier about having sex with Americans, but we partied on.

Reports were filtering through from New York and Los Angeles about something called “gay related immune deficiency syndrome” or GRIDS. The first many of us heard about it was in July 1982. It was then that Gay News, the fortnightly newspaper, ran an item about a man named Terrence Higgins who died on the Heaven dance floor.

He was one of the first British men to die from what was later called AIDS. The Terrence Higgins Trust was established in his memory to campaign for research into HIV and AIDS and it is still going strong today.

It’s a Sin brilliantly conveys this contradiction of the emergence of a terrifying virus alongside the relentless pursuit of sexual adventure.

But then people started disappearing. Around the margins, men exited the lives they had built, retreating from friends, fired from jobs, wheeled to lonely hospitals, or reabsorbed into the families that had driven them away in the first place.

Our group wilted one by one. They abandoned the scene almost all together. They retreated, consigning themselves to a newly closeted world, fearing their chances of meeting a lifelong partner had been snatched away.

As the world confronts the Covid pandemic, caused by a virus that 12 months ago we knew little about but for which we now have numerous vaccines and health education campaigns, I am reminded how different the early days of AIDS were.

I was reminded how little anybody, including the medical profession, understood about HIV and AIDS in the early days. Even after the disease and its modes of transmission had been correctly identified, fear and ignorance of ‘The Gay Plague’ remained widespread. I remember well the terrifying ‘Tombstone advert’ with the message that ‘Ignorance Kills’.

It is hard to imagine the pervading environment of ignorance and prejudice, fuelled by homophobic papers, such as THE SUN. There were discussions on the TV and the radio about the risk of catching AIDS from a lavatory seat, from taking communion wine, or at a swimming pool. I remember distinctly people not sharing a glass with me. There was hysterical talk from politicians about containing AIDS patients in leper-like colonies.

I would go and get tested regularly but always in fear I would be spotted at the clinic. I had registered myself under a false name, such was the terror of losing my job, and, more practically, in case I wanted to get a mortgage. And how I remember the heart-stopping suspense of waiting two weeks for the test result. To obtain my first flat, bought with a friend, I had to get an endowment as I could not get a mortgage, because insurance companies would not insure two men.

A beautiful boy called Paul Reeves attended the same gym as me. He was a dancer who had appeared on Top of the Pops and was at the time in the roller-skating musical Starlight Express.

Normally the very image of muscular health, I was shocked to see him in the changing rooms one day looking like a skeleton. Here was the face of AIDS in front of me. Looking at him in the changing room I was shocked to see how much weight he had lost. His averted his eyes, spoke of the shame he felt. Weeks later I found out he was dead.

Another musical theatre actor, Martin Smith (Che in Evita, Les Miserable, Phantom), was next. I remember seeing him in his last role in City Of Angels before he was forced to give up theatre.

The West End theatre scene seemed decimated as chorus boy, dancer and leading actors fell one after the other. We learnt how to surreptitiously decide on someone’s health. Weight loss was disguised, KS lesions were covered with make-up, drastic lipodystrophy was filled with filler.

James McClosky, a cute little Irish pixie of a boy, who was a window dresser by day but danced in Matthew Bourne’s amateur productions before Matthew was known, was next. James had been my first boyfriend in London.

Visiting him in hospital and listening to him planning to travel the world when it was obvious by his emancipated frame that he had weeks left to live was heart-breaking. James was given a stand-in role in Four Weddings and a Funeral by Duncan Kenworthy. He did not live to see the opening of the film, which to this day I avoid watching, as you can see him, so weak, in the film.

And then there was Dursley. Although he did not tell his parents until the very end, he was open about his diagnosis among friends and work colleagues.

He had been given a dream part on television as the scatter-brained young private eye in Just Ask for Diamond, which perfectly suited the fun and lightness of his personality.

His immune system was hugely weakened as he had virtually no T-cells left. In fact, he joked that as there were so few he could actually give them names. An alarming effect of his low immune system was the presence of a viral skin infection caused by the virus molluscum contagiosum. This caused his face to be covered in large, raised pearly lumps that could not be hidden on television and it ended the series.

The ambition and energy which he could no longer put at the service of his career, he now dedicated to the cause of AIDS relief. Allied with a strong will and an urgent sense of mission, they made him one of the moving spirits behind West End Cares, the theatrical wing of the Aids charity Crusaid.

Alongside Jill Nalder, and Jae Alexander, he could be found in cabaret nights at Smith’s restaurant in Covent Garden, when members of the casts of the big West End musicals put on their own home-grown shows often to brilliant effect.

Much like the character of Ritchie, Dursley wanted to try everything and anything to prolong his life. He would push his doctor Mervyn Tyler hard for any treatment, and such was his belief that he could recover, he visited a variety of non-medical spiritualists, homeopaths, crystal healers and other quacks, certain that he could overcome AIDS.

Cameron Mackintosh was especially kind to and supportive of Dursley. He continued to employ him in the company of Phantom Of the Opera, despite him being so ill and often unable to perform.

The night before his 30th birthday, and weeks before he died, Cameron allowed Dursley to perform as Raoul. How Dursley pulled this off, I don’t know, but he was brilliant.

His last days in hospital, buoyed by copious amounts of morphine, had a feel of a party. Jill, who if you see the series, dedicated herself to Dursley’s care, dexterously managed his many visitors, making sure he was not overwhelmed. However, there were times when there were visitors sitting in every part of his room, listening to Dursley coming up with song choice after song choice for his funeral.

In fact there were so many song choices that Kim Criswell said, at his memorial at the Actors Church in Covent Garden, “The only way I’m going to do this is to sing a medley”. She then cursed him for choosing ‘And I am telling you I’m not going’ as it is so hard to sing.

And Dursley has not gone. This photograph sits in my flat. And his energy seems to live on. Olly Alexander captures Dursley’s sense of mischief, his bravery and his spirit brilliantly. And thanks to Russell T. Davies, there is a film document of this very sad period of our young lives in London in the 1980s.

“It was such fun,” says Ritchie as he lies in a hospital bed, dying of Aids. “That’s what people will forget. That it was so much fun.”