from Labour Hub

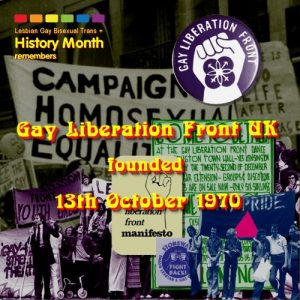

The first meeting of the Gay Liberation Front was held 50 years ago this month. Jeff Evans reflects on the long struggle for LGBTQ+ rights

As a ‘sissy’ child of the 1960s and ‘70s living in a former Lancashire mining village, the birth of the Gay Liberation Front(GLF) generated no direct impact on my own attempts, or those of many in my situation, to understand growing-up amid a very formal reading of love, sexual attraction and identity. Indeed, masculine performance and the rigid policing of binary gender stereotypes was the iron-clad norm, although sex between lads was quite common within strict rules.

However, that is not to suggest that pioneering groups such as the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) and the much shorter lived GLF did not subliminally impact on us in our remote northern village and much more importantly in our later lives. For my community, sexual terms and talk of the physicality of sex were still largely taboo and thus deeply embarrassing to even think about. My mum used to get up and put the kettle on if a couple kissed on TV! The level of sexual ignorance maintained and policed by the community about reproductive sex, parts of the body, sex acts, etc, was by today’s standards astonishing.

In the late ‘70s Mrs Davis, my best friend’s mum, ‘became a lesbian’, providing the village with a wealth of gossip on which to feed for months. My own mother in a candid comment expressed no surprise at the news, her school friend having always been a little boyish. It was a classic example of the gender binary providing the only conceptual framework by which to try and understand human gender and sexual diversity. There was sympathy expressed for the husband but little attempt to broaden the insight beyond the personal.

However, it is difficult to ignore and impossible to dismiss the contributions towards more informed public discourse of the GLF and CHE, together with, and perhaps more importantly, the increased public agitation for women’s equality, the growing power of working class organisations, for example, the Shop Stewards Movement, and institutional reforms, such as the Sexual Offences and Abortion Acts.

Perhaps one of the more lasting impacts of the brief period of GLF agitation and ‘gay’ theorists such as Dennis Altman was on working class movements and thinking. Gender and sexual equality had always been part of the early socialist movements. The German labour movement parties had promoted gay equality legislation in their policies in the inter-war period. Indeed, the huge Germany Communist Party had been the last to surrender to Stalin’s rejection of such reforms. One of the achievements of the GLF was to have encouraged GLF member and historian Jeffery Weeks, together with Sheila Rowbotham, to uncover and celebrate the work of the Sheffield-based socialist and sexual equality advocate Edward Carpenter. It might also be seen to have had a role in Jeffrey Weeks’s astonishing pioneering efforts to help generate the flowering of LGBT+ history that has emerged over the last fifty years here and internationally. Weeks was one of the first people to try and marry left wing and gay theories in the Gay Left magazine (available via the internet).

More broadly, what CHE and perhaps the more theoretically orientated GLF also did was to strongly influence and assist the labour movement to develop a political synthesis between socialism and sex/gender. The early Labour Campaign for Gay Rights was a tangible product of this development within the Labour Party and trade unions. It is the libertarian aspect of ‘Gay Liberation’ that validated new ways of understanding human diversity and developed a proto-vocabulary with which to do so. New ways of assessing and validating links between differing movements and identities became possible in a way that the older Marxist politics made difficult or formulaic. Within the labour movement, that move towards a more responsive socialist reading of human/LGBT Rights was played out in one of the largest Labour Party Sections of the 1980s – the Labour Party Young Socialists (LPYS).

The highly successful and large LPYS organisation of the 1980s was dominated by supporters of the Militant newspaper, who promoted a very dogmatic ‘petty bourgeois’ theory of ‘gay love’. As a member of the LPYS, I and other ‘gay’ members formed Lesbian and Gay Young Socialists (L&GYS). Each year we’d head off to LPYS Conference and the Forest of Dean LPYS summer camp and spend our days in debate and informal discussions assailing the Militant’s ‘petty bourgeois’ theory.

This practical orientation towards a more flexible, inclusive left wing reading of sex and gender was given an opportunity to shine with the coming of the miners’ strike of 1984-5. The L&GYS group quickly folded into Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners, celebrated widely and showcased in the film Pride. The outcome of that activism is credited with the Labour Party’s adoption of progressive lesbian and gay policy at annual conference, proposed by the National Union of Mineworkers President Arthur Scargill. Arguably without this shift in Labour Party policy, the swift progress of the LGBT+ agenda might have been much slower.

The influence of the GLF’s expansive provocative readings of sexual liberation may not have been the direct impetus that made all this possible. However, what appears clear is the CHE and especially the GLF provided a theoretical challenge to the more thoughtful section of the left which helped to provide a wider space in which the debate might grow and a history be created.

For young activists such as myself, the GLF had extraordinarily little direct effect on our lives or the working class communities in which we lived. However, on reflection, what the advocacy of these early movements did was to provide a wider theoretical environment in which traditional harmful taboos that warped people’s lives might be questioned and rejected. This theoretical challenge has radically changed the left and caused a far more critical and deeper understanding of our human condition and its needs to better promote a pathway for a more fulfilled and peaceful existence.

Jeff Evans, now a Research Fellow at John Moores University, Liverpool, has been an active campaigner for LGBT+ and human rights for the past 40 years. He founded Outing the Past in 2015 and has recently completed Project Management of the first retrospective touring exhibition of LGBT+ activism in Northern Ireland, Queering the North, with the Museum of Free Derry.

Image: Source: Support the Miners at London Pride 2015.Author: David Jones, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.