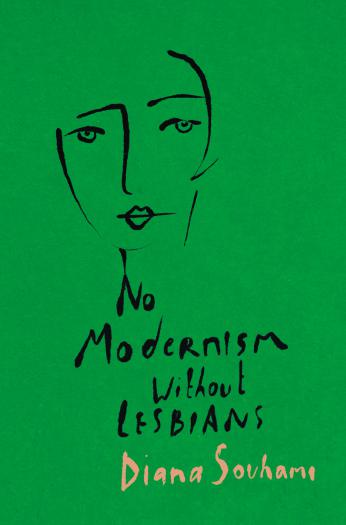

Review of “No Modernism Without Lesbians”,

by Diana Souhami

Sue Sanders for LGBT+ History Month, May, 2020

It was back in the eighties when I went to the British Library to start my research on lesbians which I had discovered in the very coded descriptions of Dale Spenders’ book, “Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them”. I was desperate to discover what lesbians had achieved before me, who they were and how had they acted in the world. I was an angry feminist lesbian trying to make sense of my life under patriarchy. The British Library was not much help. I was befuddled by the Dewey system and requests to the staff asking about lesbians were received with cold looks and little help.

However, I did discover the coterie of lesbians who went to Paris in the early 20th century to escape the strictures of the USA and Britain. I was both excited and shocked by what seemed to me then, their rather hedonistic, self-centred and privileged lifestyles.

I have read most of Diana Souhami’s previous books about several of these women. She enabled me to re-evaluate the legacy of these lesbians such as Gluck, Stein and Trefuse and to recognise that their lives were not as self-indulgent as I had thought.

This book, “No Modernism without Lesbians” forces me to further consider the roles of these lesbians in forming a cultural movement. Diana has chosen four lesbians to spotlight: Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, Bryher and Natalie Barney. In her introduction Souhami quotes Virginia Woolf to Vita Sackville West, “Throw over your man, I say, and come”. She posits that these women/lesbians/bisexuals/trans and all the others she so skilfully weaves into the book were challenging patriarchy by their very existence and choices. She also makes the case for considering their roles in nurturing and supporting in many ways, the artistic movement known as ‘Modernism’. To quote Kathleen Kuiper: “Modernism, in the fine arts, a break with the past and the concurrent search for new forms of expression. Modernism fostered a period of experimentation in the arts from the late 19th to the mid-20th century, particularly in the years following World War I.”

The book’s premise, “No Modernism Without Lesbians” is a bold assertion and one that has caused a stir amongst historians. Diana’s choice of women depicts the variety of ways that these lesbians contributed to and cradled the movement. Bryher and Beach primarily sponsored artists, giving them financial, residential and emotional support. Stein, like Barney held regular salons where artists met, networked and built their reputations. Both women were artists themselves; Stein was a writer and Barney made her life her work of art, as she proclaimed.

Souhami’s wealth of knowledge about all these lesbians and their intricate circles within circles is vast. The index is a who’s who of the rich, famous, infamous and should be knowns, of the times. Souhami makes it easy for anyone to follow up on these lesbians by providing us with a meticulous amount of information, image credits, citations, references all the books she used, and tells us where the archives are. She gives us lists of the works of each woman. This is a gift in itself and I hope will enable and inspire readers to produce plays, films and other writings so these extraordinary lesbians become better known and celebrated. She has enabled us to learn as she says, “to see what lesbians achieved and can achieve when, collectively they dictate their own agenda.”

I am in awe of how she organised all the facts, stories and quotes and then so deftly wove them, so we can see the glittering patch work of interlinked lives, broken threads and startling colours laid out before us. It is a challenging read because of its complexity, and it is a magic carpet that takes you into Paris at an extraordinary time of creativity and hedonism. It was the perfect book to read now, as I sit in quarantine. It engulfed me in a different century, and I became enthralled with their lives, concerns of the heart and their determination to take some power in the world of publishing.

Gertrude Stein arrived in Paris, 1903, from the USA to join her brother. She was one of the first people to buy a ‘Picasso’ and for a while they were close friends. Picasso’s portrait of Stein took eighty to ninety sittings because they talked so much. Gertrude thought their artistic intentions were similar – “to change ways or expression in art – she in words and he in paint, to move on from strictures, structures conventions, expectations and limitations to take risks and break moulds.” Her brother turns against them both, calling their efforts “God almighty rubbish,” “haemorrhoids, cubico-futuristic tommy rotting”. Stein disagreed with him and said they sought “to express things seen not as one knows them but as they are when one sees them without remembering having looked at them”.

Together they got to know Matisse, and Cezanne and buy their works. They also purchased works by Toulouse- Lautrec, Bonnard, Vuillard, Gauguins and Renoirs. They bought them because as Souhami says, “for Gertrude, their ideas – resonant in their work — new ways of seeing and departure from received forms of expression, echoed her own thinking.” (If you have not read Stein this may not make sense.)

Steins says, “Cezanne gave me a new feeling about composition. I was obsessed by this idea of composition. It was not solely the realism of characters but the realism of the composition which was the important thing. This had not been conceived as a reality until I came along but I got it largely from Cezanne.”

Souhami’s chapter on Stein further demonstrates clearly to me how she was both involved and supportive of the new ways of working in the visual arts. She was herself an author of modernistic literature and she supported other writers of her era. She was a great friend to both Hemmingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. They sought and valued her opinions of their work.

Gertrude’s work was not always understood or valued by her fellow countrymen and getting it published was often an arduous process. It is worth noting that however, that her ‘Four Saints in Three Acts, became an opera with Virgil Thompson writing the music. It was performed with an all-black cast in 1934, at the Atheneum Theatre, New Haven, Connecticut, a part of the New York metropolitan area. It was a smash hit, and as Souhami says, “while fascism was eating at the heart of European civilisation, ‘Four Saints in Three Acts’ rang out — zany, inclusive, playful joyful and open.” Such a different America from the one Stein and the others had fled earlier. Souhami, makes it clear just how hard it was for books we now take for granted, to get printed. So many of them were published due to support of lesbians.

Sylvia Beach also arrived in Paris from America in 1903. But it was not until 1919, after she had discovered A. Monnier’s Bookshop. Adrienne was to become both her business and life partner. She soon set up her own bookshop across the street in St Germain, the famous ‘The Shakespeare & Co’.

Diana states “Making money was not the prime consideration. Neither of them was much good at that. Both loved books and their authors. Books were essential to civilised living. Both saw their work as contribution rather than commerce.” Beach’s intention was to specialise in modern innovative writing in English. The shop acted as a lending Library and a welcoming meeting place for authors. “Customers did not want to only buy books – she might have made some money if they had. Shakespeare and Company quickly evolved into a bookshop, library, a book club, bank, post office, hotel, referral agency, and a place to meet and talk about books and life and have tea. Her fame lasted for the whole tenure of Shakespeare and Company right up until Hitler’s Nazi army closed it down and interned her in 1942.”

Souhami went into detail about how Sylvia became involved with James Joyce. It was her unfailing support that enabled him to be published. She picked up the torch from other lesbians, Harriet Weaver and Dora Marsden, who had tried to serialize Ulysses in their literary magazine, ‘The Egoist’ which was England’s most important modernist periodical. Two other lesbians, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, had also wanted to serialise the book in their New York magazine, ‘The Little Review’. They published 23 instalments. On no less than four occasions, posted issues containing Episodes of Ulysses were confiscated and burned by the United States Post Office based on allegations of obscenity.

Beach spent years and money she could ill afford to get Ulysses published. So much time and energy that her relationship with Adrienne was threatened. Bryher sent her money frequently to enable her to stay afloat. Ulysses was finally published in 1920, and banned in both England and the USA. In response to the publication, another lesbian, Harriet Weaver, got involved in attempting to distribute it in England, only to see 500 copies being burned in the ‘Kings Chimney’.

As an unintended consequence, Beach gained a reputation as a publisher and vendor of pornography. Many writers of books, censored as obscene, asked to be published by her. Richard Aldington and Aldous Huxley attempted to persuade her to publish DH Lawrence. She declined. Diana tells us, “Tallulah Bankhead’s agent asked if she would publish Tallulah’s memoirs. Sylvia doubted she would have turned that down, but no manuscript arrived. Tallulah’s name, like Greta Garbo was another link in the daisy-chain of famous lesbians.”

Souhami tells us, “Bryher felt trapped in the wrong body. Even as a child she viewed her birth gender as a trick, a mistake. She saw herself as a boy who needed to escape from the physical cage of a girl. She was tormented by pressure to have curls, wear frocks, be called by her birth names, Annie Winifred, or her nickname, Dolly….… Bryher did not want the patronymic of her father, the matronymic of her mother or the name of any husband of convenience. Bryher is one of the Isles of Scilly, off the Cornish Coast, a part of the world she came particularly to love.”

She was born into great wealth which she used to support artists and was a

patron of the modernists. Of herself, Bryher says, “I have rushed to the

penniless young, not with bowls of soup but with typewriters.” Diana credits

Bryher as ‘the rock and saviour of her partner, the poet, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle). She funded the Contact Publishing Company in

Paris, supported James Joyce and his family with a monthly allowance, gave

money to Sylvia Beach and subsidized Margaret Anderson’s ‘Little Review’, in

New York. She started the film company POOL

Productions in Switzerland, financed its experimental films and founded ‘Close Up’,

the first film magazine in English. She built a Bauhaus-style home in

Switzerland. She supported the emerging psychoanalytical

movement in Vienna, and funded Freud and other Jewish intellectuals hounded by

the Nazis to help them get out of Germany and Austria.” Formidable accomplishments made possible by

her great wealth and passion like Beach’s and Monnier’s, “to be of service.”

Natalie Barney, the fourth focus of Souhami’s book, says “Love has always been the main business of my life”. Diana comments, “This main business involved lots of sex. Natalie went where desire led her. She shared her bed, the train couchette, her polar bear rug, the riverbank or wooded glade with many women, and not always one at a time. Modernism in Natalie’s life upended codes of conduct for sexual exchange. For Natalie, modernism meant lovers galore. ”Barney was another rich refugee from the puritanical attitudes of the United States. Like Bryher, she was very wealthy; however, she did not share the same passion to be of service, she was far too busy being busy. As she says, “The finest life is spent creating oneself, not procreating”. She was, however, a walking visual aid of queerness. Souhami puts it better, “Her inspired contribution was to be transparent about same sex desire in a repressed and repressive age. Too impatient, privileged and self-occupied to give much time to a task or a cause, she led by candid example. Many women followed and were liberated by her courage.”

The list of her lovers includes many poets, writers and artists of modernism who she brought together to learn of each other’s works and ideas in her regular and extremely popular salons. She had a house in Neuilly and in homage to Sappho staged tableaus there. Diana says, “she sketched her rules for sapphic love: ‘women were to relinquish ties to family — husbands, children and country — and instead write, dance, compose and act on their love and desire for each other’.”

This was easier for some women than others, of course and possible for her as she had inherited the equivalent of about $75 million in today’s money! It is perhaps difficult to imagine the world she inhabited and created but as Souhami plainly says, she created “the Sapphic centre of the western world.”

The list of lesbians who frequented her homes is long and what follows is by no means comprehensive: the Hellenist Evelina Palmer, the courtesan Lianne de Pougy, the poets Lucie Dearue-Marrus, Rene Vivien and Olive Constanve, the writers Lily de Gramont, Colette and Djuna Barnes, Dolly Wilde, Radclyffe Hall, Gertrude Stein, the portrait painters Romaine Brooks and Gluck, the patron and socialite Nancy Cunard. These serve to demonstrate the ‘daisy chain of dykes’ referred to by Truman Capote. The richness of this book is that as well as Souhami’s choice of these four women she included a myriad of other lesbians who were active at the time and in and out of each other’s lives, beds and creativity. It is also a treasure in that she has done so much work in researching and documenting these lesbians and their archives, she deserves our massive thanks. That so many of the lesbians included will be unknown to me and you, is an indictment of our education and media. To bring them all together on one book in such a lucid and entertaining way is a valuable achievement. I am eternally grateful to her in pointing out not only their creativity and roles in birthing modernism, but also depicting their political work. They deserve our admiration for being out lesbians at a time of great oppression, active volunteers in wars caring for the wounded and as rescuers of people from certain death by facilitating their escapes from the Nazis. Diana Souhami has unearthed and brought to life a fascinating, formidable feast of lesbians of whom we can be proud when we look for role models.